Condor Trail Part 1: Lake Piru to Dry Canyon

Day 1 | May 15th, 2025

7.5 miles

It’s the kind of place you might miss if you blink, but the downtown stretch of Piru has a quiet charm; sun-bleached signs, peaceful streets, and a handwritten blackboard outside a little restaurant called Nikki’s Casamia Restaurant & Catering that reads “Open” and “Pupusas.” We park without hesitation, go inside, and place our order at the counter: two pupusas and one huge burrito.

Inside, a group of customers occupies one of the back tables. It’s a small, intimate space. A TV plays the local news, but no one seems to be watching. Cosmo and I sit near the counter and wait. The group in the back chats and jokes around with an ease that makes it clear they all know each other, probably regulars.

As we wait, I look out the window and see an employee walking down the street, hand-delivering a to-go order to a nearby home.

We left Los Angeles that morning, always a longer process than it should be, and after about an hour of driving, the scenery shifts from endless sprawl to scrubby hills, farmland and open space.

We take our food to go and drive about six miles to the Lake Piru gatehouse. We tell the staff we’ll be parking a car at the Pothole Trailhead for a month while hiking the Condor Trail. They’re friendly and nod when we mention the Condor Trail, but I’m pretty sure they don’t really know what we’re talking about. Nobody hikes the Condor Trail.

From the gatehouse, it’s about five miles on Piru Canyon Road to the Pothole Trail / Condor Trail trailhead. The parking area is a moderately sized dirt lot with a trail sign and a bathroom. We are the only car. We park, eat our burritos, and set off.

The hip belt pocket on my pack breaks before we even start hiking, which feels like a warning. We ignore it and start anyway.

Right away, the trail is lined with poison oak, demanding our full attention. We know this route includes overgrown stretches, but we don’t expect that part of the challenge to start so soon. About a quarter mile in, while trying to find a way around a thick patch of poison oak, we realize we’re not even on the right trail. Actually, we’re not on any trail. How did that happen? Oh, boy. We backtrack to the parking lot and start over.

Turns out the trail is not directly adjacent to the parking area. We walk a short distance from the parking lot, further up the road, until we see a sign that says Pothole Trail with an arrow pointing toward the trail, which looks more like a faint path through the grass than a proper trail.

The trail climbs over 2,000 feet through fields of wild grasses and yellow Shortpod Mustard, some nearly as tall as I am, brushing against me as I move. It seems like perfect terrain for a mountain lion to lurk, a rattlesnake to hide, or more likely, for ticks to hop on and hitch a ride. I hate worrying about ticks while I hike.

The trail is unmaintained, sometimes nonexistent, and steep. I stop a few times to catch my breath and look back. The higher we climb, the smaller Lake Piru appears behind us, while the landscape stretches wider and more vast. I spot a black bird soaring overhead and pull out my monocular. A condor on day one?!

It’s a turkey vulture.

I look ahead and see Cosmo pushing through the grass effortlessly. How does he get so far ahead so fast?

We reach the top of the climb and enter Sespe Wilderness, marked by a weathered USFS sign.

From this point, a narrow singletrack dirt trail heads north, winding down the ridgetop toward Agua Blanca Canyon. The trail is surprisingly smooth and well-defined, offering fast, flowing miles with just enough twists and turns to keep things interesting. We don’t know how often we’ll get smooth trails like this, so we stay grateful but not attached as we enjoy the speedy miles.

As we descend, grassy, flat meadows spread out below, framed by rugged hills on all sides. We see plenty of cat poop, a few horned lizards, a skunk, and the biggest pile of bear poop either of us has ever seen.

We pass Pothole Spring and an old tin cabin, which the guidebook says is one of several privately owned properties scattered throughout the national forest.

As we descend deeper and get closer to Agua Blanca Creek, the poison oak patches grow thicker, sometimes becoming impossible to avoid. "Pants time," I decide, slipping my waterproof rain pants over my shorts. The fabric clings to my sweaty skin, and the little scratches on my legs sting, but the protection is worth it.

The trail eventually drops to Agua Blanca Creek, which flows clear and cool, winding through a shaded canyon lined with oak and sycamore trees. Its rocky bed forms small pools and gentle riffles, surrounded by lush vegetation that sharply contrasts with the dry hills above.

The Agua Blanca Trail is not well defined, marked only by sporadic cairns. It crisscrosses the creek multiple times, and the rocky bed makes for difficult footing, significantly slowing our progress.

We try to follow any semblance of a trail, but it’s a fruitless effort. We spend a lot of time skirting thick patches of poison oak. More often than not, we end up slogging through the creek just to keep moving and make navigation easier. The only upside is hoping the water rinses off any poison oak oils as we go, fingers crossed.

It’s been about an hour since we reached Agua Blanca, and we’ve barely covered a mile, probably less. It’s after 7:00 p.m., and we’ve had enough. We stop at Hollister Camp, an old historic site that’s really just a flat spot surrounded by grasses and sagebrush.

We rinse off in the creek and share a light dinner, still full from the earlier burrito. Afterward, we lie in our sleeping bags, hearing crunching and other noises all around. We do an eyeball check but see nothing. We remind ourselves to get into the habit of nightly tick checks, so we do that too, all clear.

We're tired and fall asleep quickly.

I wake up thinking I've slept through the night, but it's still dark outside. Checking my phone, it's only 2:30 a.m. I lie awake for a while staring at the sky. I wish I could say I watch the stars or something poetic, but without my contacts in or glasses on, it's just a dark blur. Eventually, I fall back asleep for a couple of hours.

It's only day one, but already we're deep into this all-consuming adventure.

Day 2 | May 16th, 2025

7 miles

We spend most of the day wading upstream in Agua Blanca Creek, following a “trail” that the guidebook and maps show winding west along the banks, dipping up and down and crossing the creek regularly.

We try to find an actual trail, scanning the banks for a faint path and looking for cairns at potential crossings. Sometimes we spot a track and step toward it, only to find ourselves boxed in by poison oak. Other times, we think we’ve found the trail again, but after a few paces, it disappears into the undergrowth like a mirage.

We move forward. We backtrack. We climb the creek banks. We brush against poison oak. We stop to try and wash the oils off, scrubbing hard, rinsing our poles, hoping it’s enough. Then we keep going.

We spend more time stopping, searching, and second-guessing than actually moving forward. Every promising path ends up blocked or lost, turning progress into a slow, frustrating slog.

The guidebook says if the trail is difficult to find, it may be easier to just walk through the creek. Nothing about walking through the creek is easy. The difficulty is deceptive. Each step is cautious and uncertain. Sometimes the water is clear enough to see where I’m going; other times, it’s murky and thick. A few steps feel smooth and steady, then without warning, my foot sinks into thick underwater mud, like quicksand. As I try to lift it, the suction grips harder, pulling back with every effort. It takes all my strength to yank it free. God damn, this is slow. And of course, we’re traveling upstream, against the grain. Naturally.

My feet stay soaked all day, the bottoms of my toes and soles looking like ghostly prunes, white and wrinkled. They ache, sliding around inside wet shoes, and I can’t keep the laces tight enough to hold them in place. Each step slips, squishes, rubs, and presses in all the wrong places. Blisters are inevitable.

Schools of fish dart around our legs. Butterflies flit through the air. I try to notice, to let the beauty soften the edges, but these are some of the hardest miles I’ve ever hiked. The wading is slow, and the ground never feels steady beneath my feet.

There is no relief. Even the biggest, most solid-looking rocks slip out from under me as I skip across. Its impossible to get into any sort of rhythm, the stop and go of it all is a bit maddening. There’s always something in this canyon, we push past poison oak, and just when that eases, we’re dodging stinging nettle.

We reach the Big Narrows, a unique geological area where the water has carved a deep, U-shaped gorge through a massive ridge. Here, we’re enclosed by cliff walls that rise hundreds of feet on either side.

It comes as no surprise that the only practical way through this section is in the creek itself. We continue wading, splashing, and slogging through countless pools and cascades. Sometimes the water reaches only our shins; other times, it's chest-high. The footing is relentlessly tricky, slippery slabs, loose cobbles, and slick algae-covered rocks make every step uncertain. We scramble over smooth, wet boulders and feel our feet slide across uneven stones under the surface, constantly working to stay upright and keep moving.

We originally planned to cover much more than seven miles today, but our bar has been lowered. If we can just make it out of the canyon before dark, we’ll count it as a win. We seriously underestimated how long it would take to get through Agua Blanca.

The sun dips lower, and we set our sights on the map at Ant Camp, a backcountry site near the junction of the Agua Blanca and Bucksnort Trails. Who knows what kind of shape Bucksnort will be in, but at this point, anything sounds better than Agua Blanca.

We finally reach the site and drop our packs in relief. Ant Camp is a quiet backcountry spot on a grassy bench above the south side of Agua Blanca Creek. A few non-poisonous oaks offer shade over a flat clearing with a well-used fire ring, makeshift benches, a picnic table (missing a slab but still functional), a rusty stove, and a shovel tucked behind a tree. Camps like this are common in Los Padres, where trail crews, hunters, and longtime users have left behind tools and infrastructure for shared use over the years. It’s just a flat spot near the river, nothing special, but it feels like a victory.

Starting to set up the tent, we suddenly spot a huge (and I mean huge!) black bear ambling toward us. It comes uncomfortably close to camp but, luckily, doesn't seem too interested. We manage to scare it off and watch as it disappears back into the woods.

When night falls, screech owls call from every direction, their whistles bouncing between the trees. The sound is a series of short, rising hoots, "hoo-hoo-hoo-hoo-oo-oo," accelerating toward the end like a bouncing ball losing steam. Cosmo and I lie still, listening in quiet awe.

Once again, I wake around 2 a.m. and lie there, this time listening to the creek, the owls, and the soft rustling of nighttime wildlife all around us. I let it sink in. Hard to believe it’s only day two.

Day 3 | May 17th, 2025

16 miles

We wake to a misty, gray morning. Clouds hang low, and the air is damp and cold. Fog clings to the trees and hillsides, smudging the view like breath on glass. This isn’t a storm or a downpour, just the quiet insistence of a slow, steady wet. It seeps into everything and adds weight to it all: our gear, our packs, and our moods.

I stay curled in my sleeping bag longer than usual, reluctant to leave the pocket of warmth I’ve built overnight. Outside is a layered chorus of conversation, birdsongs echoing from branch to branch, a world we’re not quite part of but lucky enough to overhear. I pull out my phone and open the Merlin app. It picks up seven distinct species.

If only people talking over each other sounded this melodic. More often, we’re like the arrival of a Steller’s Jay, sharp, abrupt, and jarring with that harsh caw caw.

I keep thinking about how close I came to leaving my warm layers at home. I actually considered not bringing long johns or my puffy, foolishly assuming the greatest challenge of a mid-May hike would be sun and heat. I hate packing up when I'm cold, worse when I'm wet, and worst of all, both. But here we are, and I'm grateful for every ounce of warmth I’ve carried.

We left Ant Camp and headed southwest on the Bucksnort Trail. According to the guidebook, the Bucksnort Trail is marked green, supposedly indicating an "actual trail." However, on the Condor Trail, we're quickly learning that "green" doesn't necessarily mean maintained, poison-oak free, or even clearly visible. The color system, much like other details in the guidebook, is outdated and fails to account for fire damage or years of neglect. Just because a trail looks friendly on the map doesn't mean your ankles won't vanish into the overgrowth.

We ascend steeply out of the canyon carved by Agua Blanca Creek, sometimes losing the trail, often pushing through brush as we climb. Rain falls, then subsides, then falls again.

I stop to fill up water, pulling out my not-quite-new Salomon filter and little bottles of Aquamira water treatment. I like using the filter for quick sips on the go, saving Aquamira’s two-part chemical system—Part A and Part B—for treating larger amounts. You mix them, wait five minutes, add the mix to your water, then wait fifteen more before it’s safe to drink.

As I measure out Part A, I notice thick white chunks floating in the otherwise smooth yellow liquid. I walk over to Cosmo and hold it up. “Does this look right to you?”

He squints. “I don’t know…”

I sigh, already kicking myself. I know the answer: no, it’s not normal, and no, I can’t use it. With no internet to consult, we decide to play it safe. Always double-check your gear before a big hike. Always.

I watch Cosmo filter water with his brand-new BeFree. The water flows through effortlessly. Why didn’t I just start with a new filter? I think, as I squeeze meager drops from my older Salomon, pinching the mouthpiece like I’m milking a tiny cow. It works, but the flow rate doesn’t come close to Cosmo’s. It’s painfully slow, definitely not sustainable for the long haul. Another lesson learned.

At the junction with Alder Creek Trail coming up from Dough Flat, the trail conditions abruptly improve. We later learn that Alder Creek has been a big focus of Los Padres Forest Association (LPFA) since 2022. Volunteer crews (and a professional one) have spent thousands of collective hours working this trail for the past few years, with a hitch as recently as a month ago. It was like stepping onto a red carpet. Despite the rain and low clouds that blocked any potential for the lush and expansive views we knew to be here, we were made exuberant by this smooth, wide tread and clear path ahead.

We pass the surreal and incredibly fascinating sedimentary stone at Stone Corral, descend to Alder Creek (where we take a snack and a sit), and make the satisfying climb to Sespe Saddle.

With the terrain now demanding less attention, my mind drifts into its usual loop: body scans, food, images of my cat at home, existential questions, noticing the scenery, then back to the beginning. Somewhere in that loop, my focus shifts to a hot spot on my foot. Actually, several. My feet are a mess: sharp stabs from blisters and “toe mohawks,” tender arthritic big toes, and sore little muscles, all made worse by days of wet socks and uneven ground. Now that I’m finally on a clear trail, I expect relief, but the pain hits instead. The creek crossings and scrambling had kept me too distracted to notice how bad my feet were. Like sediment stirred up in a stream, once the water settles, everything beneath the surface comes into focus. Now that I can simply walk, I feel it all.

Before we left home, I bought a new pair of Altra Olympus shoes, the same model I used last summer on the Sierra High Route with no problems. But this pair feels different: much narrower and tighter through the midfoot. The shoe hugs too close in the middle, stretching the fabric upper so the skin around my arch bulges over the edges, like a foot-shaped muffin top. I hate when shoe companies release a new version of the same model but instead of just improving the grip or adding a new color, they completely change the structure. It feels like a betrayal, like they’re selling you an old friend who turns out to be a stranger that doesn’t fit. Now I’m stuck out here with these shoes, no easy way to swap them, trying to push through despite the squeeze. I’m mad at myself for not breaking them in more or testing them before the trip, but I figured they’d be fine.

I keep thinking about stopping to tape up the worst spots on my feet, but I’m afraid of falling too far behind. The trail snakes along the hillside, curving around the canyon, so I can see the path ahead. In the distance, I watch Cosmo moving smoothly, gliding along the trail like it’s nothing. I don’t want to stop, I want to move like that, light and easy.

The trail dips down to the Sespe River, and I catch up to Cosmo. I take the chance to remove my shoes and tend to the hot spots. My Leukotape is old and won’t stick like it should. I have to press it down carefully and hold it in place, making sure it doesn’t bunch up under my socks or fold over itself. I try to put my shoes back on, but it’s a struggle, like forcing a tiny glove onto a giant swollen hand. I jam my heel into the shoe and flatten my foot, but I can tell the Leukotape has shifted. Fuck it. Let’s go.

We continue on the Sespe River Trail, a well-maintained and frequently traveled route. We've been here before, so we knew what to expect and appreciate how well cared for the trail is. It's popular for good reason: fairly easy to navigate, with great views of a superb canyon with lush hillsides, and hot springs. From this point on, we are no longer alone. This is where the crowds start, and soon the groups get bigger. It feels strange to suddenly be sharing the trail with other people. Then again, it is strange to have an actual trail at all. I guess if you build it, they will come.

We camp near Willett Hot Springs, on a sandy flat by the river. We skip the actual soaking—both here and at Sespe, partly because of our focused agenda, but mainly because we’re concerned that the hot water would open our pores and worsen the poison oak that we’re certain is coating our skin We’re having visions of faces swollen with bad poison oak reactions, pussing rashes, and the painful itching. Still, I feel a pang of disappointment. I always associate hot springs with Los Padres, and now, on the biggest trek I’ve done in this forest, I might skip every chance to soak in its thermal waters.

We build a small fire and decide to share dinner. We’re both feeling uneasy about our pace, the terrain ahead, and the food we’ve got left before our next resupply. It’s the end of day three, and we’ve covered nearly 34 miles total, which is far below our estimated daily average of 17 miles. Making up the distance wouldn’t be a problem on a well-defined path, but the unpredictable terrain, hard-earned miles, and challenges that have already humbled us make it clear that rationing our food a little might be a good idea.

Day 4 | May 18th, 2025

19 miles

I finally sleep through the night and thankfully wake up to sunshine. Everything feels a little more manageable when it’s dry and clear.

My feet are still sore, and the hot spots are getting worse. I’ve covered them with Leukotape, but it never stays put. Pulling my socks on takes effort, and shoving my feet into my shoes usually peels the tape right off.

I spend part of the morning futzing with the solar panel, trying to squeeze every drop of energy out of the sun. I’m worried about more than just food, also the battery life powering all our devices. Phones, maps, headlamps, InReach (our GPS safety device), and of course my luxury item: a Flextail pump. It doesn’t have to stay charged, but it’s nice not to waste my limited energy at night blowing up my air mattress.

The trail climbs steadily, and the heat sticks to my skin. Yesterday, I craved sun; today, it’s too much. Such is life on a thru-hike. It’s easy to want warmth when you’re cold and wet, and just as easy to regret it when you’re sweating through thick brush, bitter cherry, scratchy plants, and endless poison oak.

We leave the Sespe River and head northeast on the Piedra Blanca Trail. I pick at my snacks cautiously, savoring each bite, but hunger gnaws relentlessly. My mind circles back to food again and again, how much I’ve eaten, how little remains, how long it might take to reach my bucket. Every crumb feels precious.

The trail leads us through North Fork Canyon, climbing above 5,000 feet. According to the guidebook, poison oak doesn’t grow this high, which comes as a small relief. These days are taking all my energy. While the absence of poison oak is a welcome change, the trail is still brushy in stretches, crowded with stubborn buckthorn that scrapes at our legs and slows our pace. It’s clear that trail crews have been through here, some sections are impressively clear, but the overgrowth returns quickly in places, and we feel it. The mix of relief and resistance mirrors the rhythm of the hike itself: one small reprieve followed by another challenge.

Fatigue lingers. Cosmo loses one of his sandals on the climb up from Piedra Blanca, where tangled branches reach out like fingers, snagging at packs and sleeves. He backtracks to search for it, but the climb is steep and hot. After a few switchbacks with no luck, he returns with one sandal strapped to his pack (sorry, nature —hopefully someone finds it and packs it out). My stomach growls as we climb under the mid-morning sun, the heat building, the effort constant. We’re both hungry in that steady, low-grade way that hums just beneath everything.

I stare at a cluster of ladybugs huddled together on a branch. Then I look up and realize there are thousands, maybe millions, on all the nearby branches, huddled like spilled beads tangled in twigs. It takes my eyes a moment to adjust to how many there are, and I step carefully, not wanting to crush a single one.

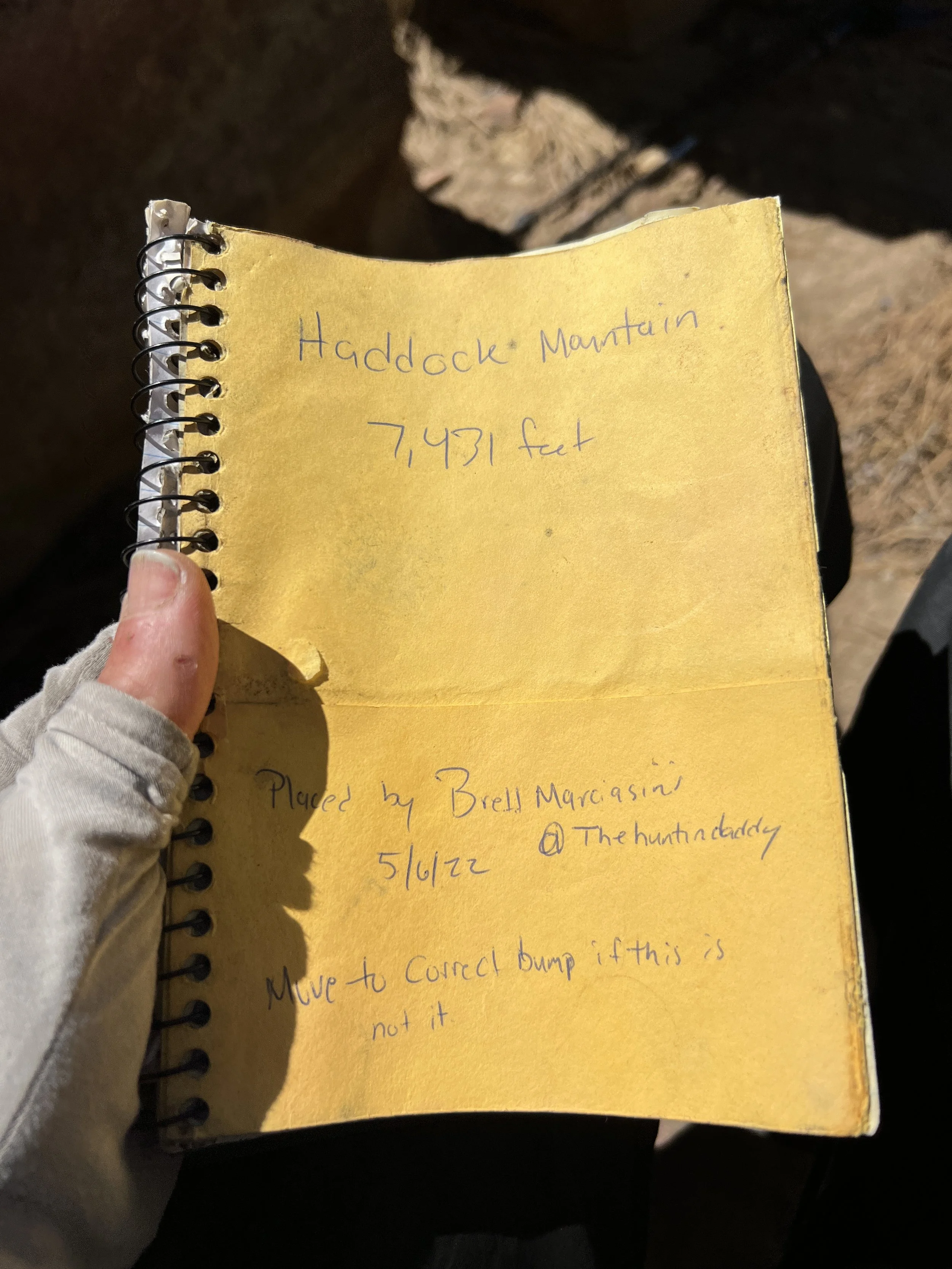

Eventually, we make it to Haddock Campground, another backcountry site. After sweating all day in the sun, it suddenly turns cold and windy, ridiculous. All I want is to sit down and eat without rationing, to zone out and snack like it’s easy.

We spot a metal box off to the side of the main camp, near the usual shovel and tools tucked away at these sites. Cosmo opens it.

“There’s some food in here.”

“Wait, really?” I look up, surprised. I can’t believe it. We haven’t seen anyone since leaving the Sespe area, deep in the remote parts of Los Padres National Forest. Who would leave food at one of these often-neglected backcountry sites?

“What is it?” I ask.

Cosmo holds up the contents. Along with a few random supplies, we find a couple packets of oatmeal, half a bag of water crackers, and a half-eaten bag of dried cranberries.

Trail magic?

Can we eat it? Should we? The usual rules we follow don’t seem to apply out here. Our standards change, what we’ll eat, how clean it needs to be, how old it is, whether someone else opened it. Hunger rewrites the rules.

This wasn’t a carefully packed cache meant for someone else’s survival. It was a jumble of random snacks, mostly opened, some half-eaten, clearly what someone didn’t want to carry any longer. A small, unexpected gift left behind for whoever came next. And today, that lucky someone was us.

We finish setting up camp, do a full tick check (pull off a few), and crawl into our sleeping bags. We delicately savor the half bag of water crackers with dinner. Never has something so dry and flavorless tasted so absurdly good.

Day 5 | May 19, 2025

15.5 miles

I finally poop. It’s been a few days, unusual for me, but after some granola and cold brew, I feel the familiar pang. “Yes!” I declare, breaking the morning silence. Cosmo looks up from packing his backpack. “I’m going to poop!”

“Hell yeah.”

The air is brisk and windy, which makes it feel even colder. I wait until the very last minute to take off my rain pants. The worry about food lingers quietly in the back of my mind, gnawing at my stomach the same way the buckthorn has been gnawing at my clothes and gear.

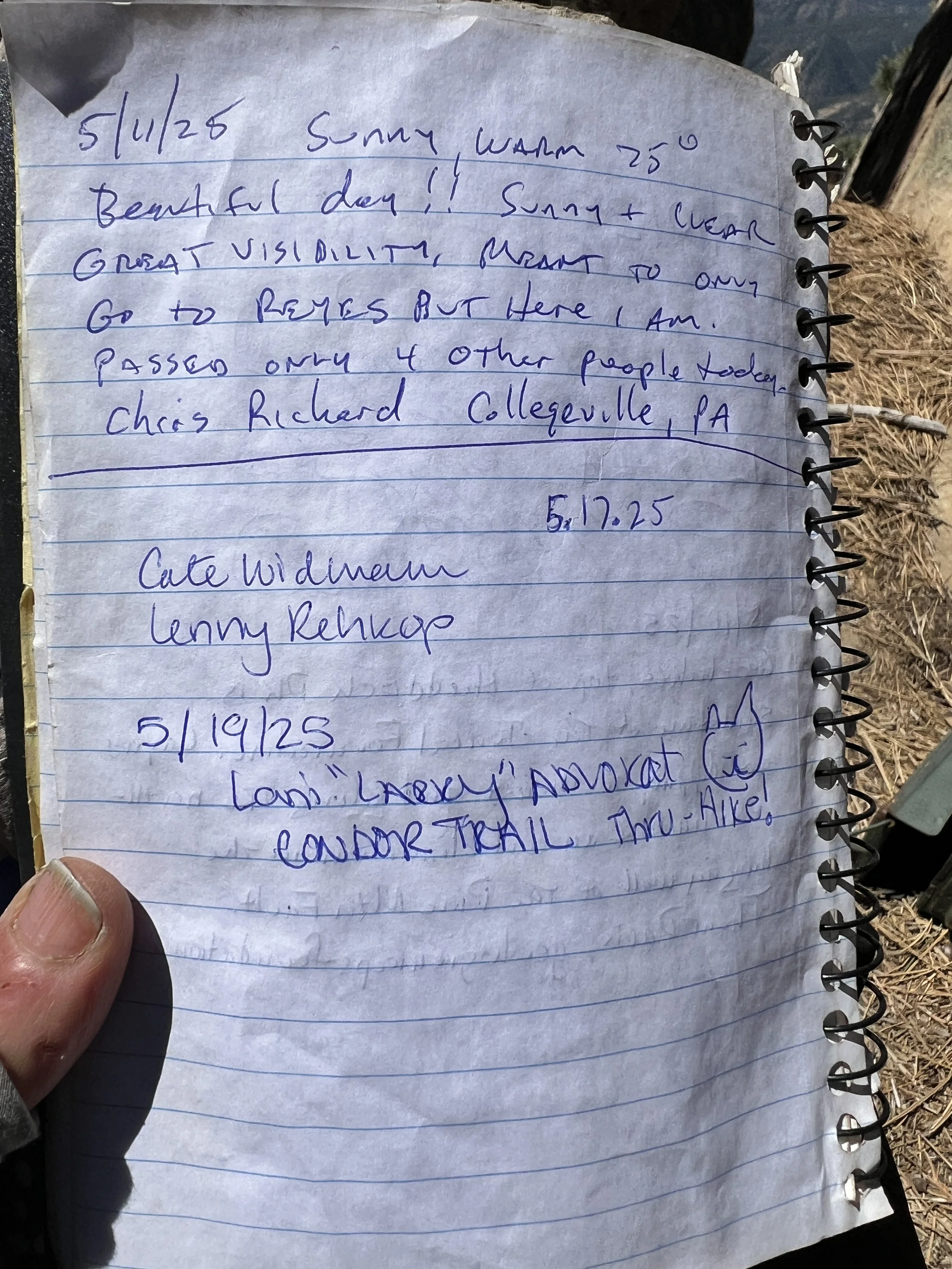

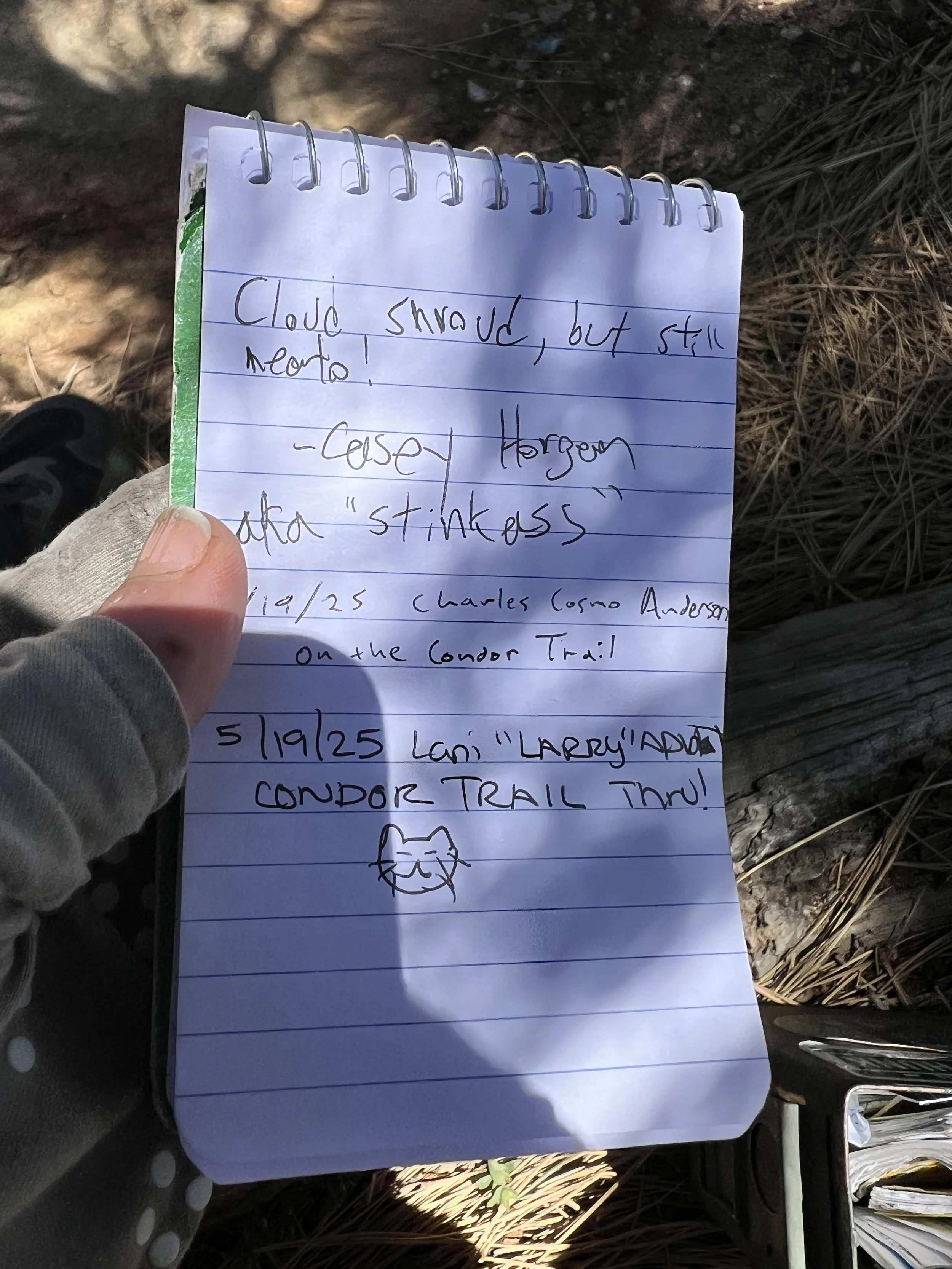

We summit Haddock and Reyes Peaks,reaching the high point of the entire route. It’s all downhill from here, right?

At the end of Reyes Peak Trail we reach Pine Mountain Ridge Road, a real dirt road. Now this is exciting. It’s like someone took three or four well-maintained single tracks and smooshed them into one gloriously wide path. I’ve never loved road walking more than I do on the Condor Trail.

My stomach is grumbling. Car camping sites line the road, and with them comes the possibility of day hikers, weekenders, and, maybe, trail magic. I feel hopeful.

We pass a few setups without seeing anyone before one camp off the road catches our attention: a large flag waves from a tree, reading, “The Forest Does Not Need Your Service.” Around it, cars are parked and tents are spread across a wide group site. Flags and bumper stickers echo messages like Free Palestine. At the main hub, currently empty camp chairs form a circle around a bulletin board covered with a schedule and task list.

It’s clearly a group site, but we only see one person, a young woman sitting in a camp chair, reading All About Love by bell hooks, with a dog curled beside her. She wears sunglasses and doesn’t look up as we pass.

Cosmo and I exchange a look.

“It’s a protest,” he says.

“Should we check it out?” I ask.

We’ve been following issues around logging and mining in Los Padres National Forest and are genuinely intrigued.

In addition to our political feelings, we can’t help but notice the full camp kitchen, coolers, and supplies. There’s definitely food here.

We walk over. The woman looks up, sets her book down, and stands. “Hi.”

She looks to be in her early twenties, with a septum piercing, dark hair, and a few small tattoos. She wears black shorts and a sports bra, her belly casually exposed. She’s friendly but quiet, the kind of person who doesn’t say much unless prompted.

“Hi!” Cosmo and I say. “We saw your sign on the road and were curious about what’s going on here.”

“Oh, yeah,” she says.

“Is this a protest?” Cosmo asks.

“Yeah,” she replies.

She tells us she found out about the protest through social media and that she’s part of a group that came from all over to protest logging in the forest, a cause we care about deeply.She hands us a pamphlet from LosPadresForestWatch.org, suggesting we check it out.

“What are you two up to?” she asks. We tell her a bit about the Condor Trail, and then we exchange names.

“I’m Bambi,” she prompts.

“Cosmo.”

“And my trail name is Larry.”

I ask if it’s okay to look around.

“Sure,” she says, walking us around the site as we continue talking.

After circling back to where we first approached her, there’s a brief pause—the natural end of the conversation, time to say goodbye. Then Cosmo breaks the silence, “Hey Bambi, we’re running low on food. Any chance you have some extra?” I’m not sure if I showed my excitement outwardly or just smiled proudly in my head. I couldn’t look up, too nervous, until I heard her say, “Umm, yeah, totally.”

She leads us to her car, just a few steps away. She smiles and hands Cosmo two packages of fig bars. Then she pulls out a big bag of almonds and asks, “Do you want to hold out your hands or something?” We both pull out empty ziplocks from our fanny packs like kids trick-or-treating as she dumps in the delicious little treasures.

The relief is immediate. Just knowing we have something extra to eat takes the edge off. We leave the campsite and continue down the road.

“You know, you don’t have to say it’s your trail name. You can just say Larry.”

“I know.”

The sun warms my face, and after days of relentless brush and poison oak, this open dirt road feels like a gift. With snacks in hand and easy terrain underfoot, everything feels a little lighter.

I know I should ration, but the fig bar? Gone immediately. I keep hiking, telling myself, just a handful of almonds. Then another. And another. By the time we’ve covered a couple miles, I’ve eaten everything Bambi gave me.

We leave the road and turn onto the Boulder Canyon Trail. It’s not a wide dirt road, but it’s clearly maintained and easy to follow, with almost no bushwhacking. The trail winds through a pleasant pine forest, offering views of Lockwood Valley and Mount Pinos.

The terrain opens up as the route follows an exposed ridgeline, no shade, no water. Of course, it’s hot now. Manzanita bushes line the trail, their large, red berries hanging in abundance. We pick handfuls and eat them one by one as we continue a five-mile descent.

We reach Ozena USFS Fire Station, a modest outpost tucked into the valley. It’s right off Highway 33, but there’s little traffic, and no one seems to be here. The first thing we notice: trash cans. We gratefully toss our trash bags, freeing up a little space in our side pockets.

“Do you think they have an outlet here?” I ask Cosmo, well aware he knows as much as I do.

“I don’t know.”

“How many days until town?”

It hits me that our first two resupply points are remote caches. Morro Bay, the first real town, is still weeks away. We won’t have a chance to recharge our batteries anytime soon, a logistics detail I clearly overlooked when planning.

My battery pack usually lasts about a week if I’m careful, but once it’s empty, it’s tough to keep it charged with just the solar panel. Suddenly, needing to recharge feels way more urgent. We’re already two days behind schedule, and with the tough terrain and slow pace, I’m starting to worry.

Every year the list of things we have that need charging just keeps growing.

We walk up to the Forest Service office building and knock. Nothing. Try again. Still no answer. It’s silent. A truck is parked out back, which gives us a glimmer of hope, but clearly no one is home.

“What now?” Cosmo asks.

“Maybe there’s an outlet on the outside of the building,” I say. “Let’s check.”

Nothing in front.

I start to tiptoe along the side of the building but quickly notice Cosmo walking away.

“It says no public access.”

“What? Where does it say that?”

There’s no fence around the building, no physical barrier stopping us from simply walking around. However, next to the building is a paved driveway leading from the parking lot to the rest of the USFS compound. That driveway is blocked by a gate with a sign that reads, No Public Vehicle Access. The sign isn’t on the building, and I’m not a vehicle, so I decide to continue.

“It says ‘No public vehicle access,’” I clarify to Cosmo as I turn back toward the building, and almost immediately I hear a loud, shrill cackling sound from a loudspeaker. We both jump, startled. It’s just a looped station report.

I edge along the side of the building, searching for an outlet. No luck. What I do find are scattered bits of toilet paper with poop on it, right there by the wall. This is a Forest Service site, the same folks who are supposed to enforce Leave No Trace. How does this happen? Not fresh, but not dried out either. I shake my head, disappointed that anyone could have been here recently and left this mess, gross.

Behind the office building I find a lone chair and some scattered gear next to a back door. It feels weirdly abandoned, like a scene from a low-budget horror movie. I scan the wall. Then I see it: a metal cover next to the door. “Yes!” I quietly say to myself. I lift it, heart pounding. Two three-prong outlets. Relief. This is perfect.

I grab our gear and rush back. I move fast but carefully, like a secret agent on a covert mission. I’m not even sure if the outlet has power, or if it will work. I plug in one wall port, then the cord, then the battery pack. It lights up. Yes!

The speaker crackles again, but I have no fear. We own this place! Just kidding. I’m still anxious, and worried that someone will come through the back door next to me any minute. I set everything up discreetly and rush back to Cosmo.

He’s at the picnic table, studying the guidebook.

“I did it,” I say, sweat soaking my shirt.

“Nice,” he says, barely looking up. Focused.

Now we wait.

Cosmo is trying to figure out how much water we’ll need and what conditions are ahead. The color-coded trail guide marks Deal Canyon with mostly green and yellow sections: green for trail, yellow for road. But, what we’ve learned so far is that out here, even marked trails can be severely overgrown, and conditions are notoriously hard to predict. We're cautiously optimistic, knowing things might not be as simple as the map implies.

We look up from the guidebook and watch as a white truck pulls into the trailhead parking lot and drives up to the gate. It's a USFS truck, and two employees arrive. We watch as they drive in, unlock the gate, and head to the back. We hold our breath, hoping they don’t spot our gear. They park in the back, struggle to unload a 4-wheeler, and barely notice us. We wave, they wave back. No one goes near the office or seems to care.

We hang back in the shade.. I notice cars passing on the highway without slowing, and the fire crew driving off without a single question. No one really sees us, or if they do, we're barely a blip on their radar. It’s a weird sensation, being a ghost in plain sight, but it’s incredibly freeing. That feeling has become a common thread on these long hikes, like we’re living a parallel life, tucked just outside the lines of normal society. And this spot is the perfect place to lean into it. It has everything we need, especially now that some of our gear is charging: a large grassy area, a picnic table with benches. It’s quiet; no one else is around. There’s a spigot with cold, potable water for public use.

We pour Mio into water bottles and drink like it’s fresh-squeezed lemonade. Somehow, artificial chemicals taste gourmet out here.

I rinse a pair of dirty socks and lay them in the sun to dry. I lie in the grass on my Tyvek, gear spread within reach. I mend my hiking pole and reinforce my backpack pocket. I dig at blisters like no one’s watching. Then I sprawl out, arms open, under a cottonwood. We’re disgusting, and we don’t care.

We stay most of the afternoon, outlasting the employees who wave as they leave. We didn’t plan to spend hours here, but it was necessary. Nothing is fully charged, and as much as I'd prefer to get everything full of juice, we can’t camp here, and the road walk ahead isn’t safe after dark. It’s time to go.

We head off onto Highway 33 for just under a mile, then veer back on a trail at Deal Canyon Trailhead. The path is faint but followable as it winds through the canyon, though the brush starts to thicken and poison oak creeps in on both sides—especially wherever we dip down to cross a streambed. After such a long break this afternoon, our bodies are hungry for movement, but as the sun slips behind the ridge, the route becomes harder to follow and the poison oak harder to avoid.

The area isn't great for camping. The only truly flat, clear spots seem to be right in the middle of the trail, a thought we briefly consider given how little traffic we've seen and our doubt that anyone would be coming by. We eventually settle on a flat-ish patch of ground just big enough for our tent and rainfly, nestled slightly off the main route. It's barely enough room. The night has fully settled, and using a headlight means a swarm of gnats and mosquitos instantly materialize, eager to fly into our faces. We're cramped, and just finding a spot to pee requires careful maneuvering around the vestibule, battling brush and the ever-present threat of poison oak in the dark.

Day 6 | May 20th, 2025

23 miles

The temperature is mild when we wake up, but there's a certain smell and feel in the air that, like a sixth sense, tells us it's going to be a hot day.

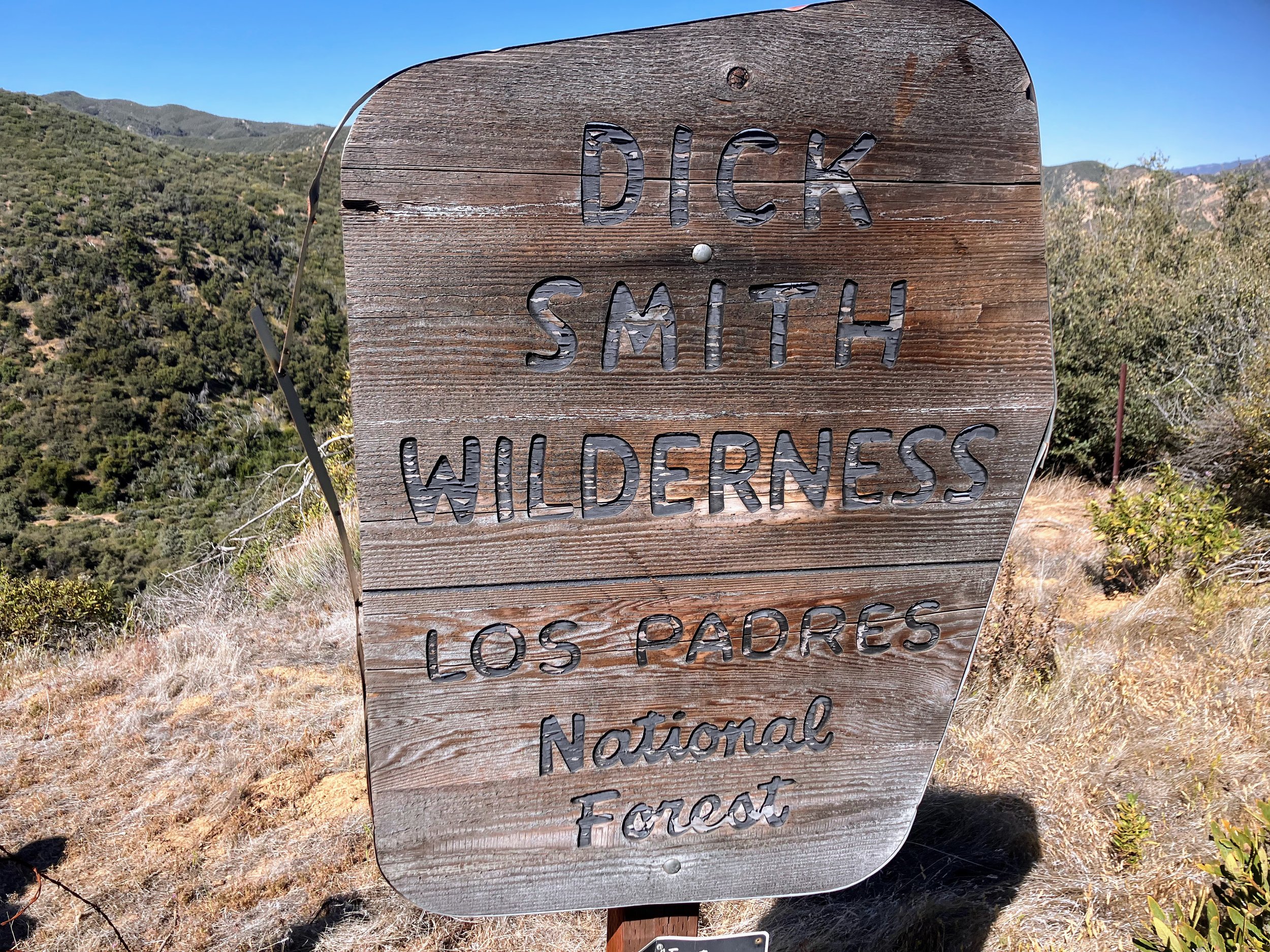

Oak-lined switchbacks lead us to a high saddle, where we enter the Dick Smith Wilderness. This expansive, rugged, and wild landscape of rolling hills, chaparral-covered ridges, unique sandstone formations, and steep canyons feels both untouched and vast.

From the saddle we descend into Deal Canyon. I enjoy the presence of an actual trail, but I know not to get too attached; in true Condor Trail fashion, it eventually fades into a bushwhack. The clear path slowly narrows, the well-trodden dirt replaced by patches of tangled brush and scattered rocks. Branches scrape against my arms as I push forward, the scent of wild sage escaping the brush while chamise pollen scatters, dusting my face.

We reach Rancho Nuevo Creek and head east on the Rancho Nuevo Trail. This section, winding alongside Rancho Nuevo Creek through Deal Canyon, is surprisingly scenic—something I notice I can appreciate better when I'm actually on a trail. The trail cuts through low scrub and dense chaparral, crisscrossing the creek several times, and winding through high sandstone walls and unique wind-carved rock formations.

At Rancho Nuevo Camp, the landscape opens up as we leave the canyon. We emerge from the dense canyon onto a parking area and old campground. From here, the route follows a shadeless dirt road headed northeast. The landscape is dry, the sky is clear, and the sun beating down feels strong. It’s hot. The kind of dry heat that sucks the moisture out of your skin before you even get a chance to sweat. I reapply sunscreen to the back of my legs; the nook behind my knees feels especially vulnerable.

The dirt road is supposed to cross Rancho Nuevo Creek a couple more times before merging with Tinta Creek. We'd been passing water all morning, holding off on filling up until what we thought would be the final, most reliable opportunity. But the crossings just past the campground are already dry. The creekbed holds nothing but large rocks, sticks, and dust. The irony hits hard: after all the days spent slogging and wading through creeks, where the water constantly slowed us down—now, when we need it—there’s nothing. What if we missed our chance to fill up?

We step off the road and scramble down into the creekbed, hoping there’s water tucked into a shady bend or hidden beneath a pile of boulders. Nothing. Now we’re seriously concerned. If Rancho Nuevo is dry, Tinta Creek might be too.

We have two options:

Option 1: keep following the road and hope we hit water at Tinta. If it’s dry, we’ll have to backtrack at least two miles roundtrip to the last place we saw it flowing.

Option 2: turn around now. It’s just a one-mile round trip to water we know is there.

For context, we do have a solid water cache waiting 15 miles away in Dry Canyon with our resupply bucket. It’s our safety net, as long as it hasn’t been ransacked by wildlife or another hiker. Reaching it by tonight isn’t impossible. But in this heat, and with what we’re carrying, it’s a stretch.

We’re each down to about a liter. It’s 1:30 PM, the temperature is hot, and we are thirsty. We’ve already covered seven miles today and Dry Canyon is still another fifteen miles away. On a different trail, a 23-mile day might be reasonable. But out here, the terrain and our speed is unpredictable. For the past five days, we’ve been averaging thirteen miles a day, and that’s just an average. Some days it took all day to go seven. Our exhaustion and egos want to keep going, betting on Option 1. Nobody likes to backtrack, and maybe there will be water in Tinta. But the smart move is to turn around.

To save time, Cosmo volunteers to head back alone to collect three more liters of water. I go ahead, and then wait at the exposed dirt road junction ahead.

I drop my pack and try to finagle my Tyvek tarp around some scraggly low bushes for a sliver of shade, but it’s useless. The flimsy fabric drapes over the sagebrush, collapsed and sad, offering no reprieve from the sun’s burning rays. This dehydrating heat instantly transports me back to 2017, when Cosmo and I were slogging through a Mojave heatwave on the PCT. We’d tried taking “smart” midday siestas then, only for them to turn into sweaty, restless breaks where it felt like we were burning as much energy and using up as much water sitting still as we did actually hiking.

Here, it’s exactly the same. I pull out my book, but the sweat, the flies, and the relentless sun make concentration impossible. I pace around, hoping Cosmo comes back soon. And he does, my hero.

We continue along the dirt road heading west through Tinta Canyon. The creek is dry, and we feel validated in our decision to backtrack.

We reach the end of the road at Tinta Trailhead. Please, please don't be a bushwhack, I think.

To our relief, the singletrack trail ahead looks well-worn and maintained. Still, it's getting harder to shake the underlying stress and uncertainty about trail conditions. Out here, you never really know how long you can truly trust the terrain.

The trail climbs steadily, weaving through chaparral-covered slopes featuring red and tan sandstone outcroppings and interesting rock formations. For the most part, the trail remains well-defined. However, just for funsies, these smoother sections of singletrack are routinely broken up by short spurts of overgrown, brushy trail, requiring the use of all limbs to push through thick vegetation.

The signs say this trail is open to mountain bikes, but I honestly don't know how cyclists make it through these thicker sections without getting tangled in branches or knocked right off their bike.

Nothing says hiker hunger like collapsing in a hot ditch and sucking down soy sauce packets and spoonfuls of nutritional yeast. I’m hot, exhausted, and starving. It’s 5 p.m., but the sun still feels like it’s blasting full force. I need a break, so I pull over at Tinta Creek, still just a dry drainage, and Cosmo joins me without hesitation. We find a tiny patch of shade under a small bush, lean against the sand and rocks, and collapse onto them, using our packs as backrests. We’re about 10 miles from our first food cache and I’m officially out of snacks. I feel grateful when Cosmo shares some of his mixed nuts and bars. I dig through my food bag for anything that’ll keep me going. I find a nearly full bag of nutritional yeast, stick my spoon in, and taste it. “Not bad,” I say to Cosmo. Before long, we’re just eating it by the spoonful. Then I find a couple soy sauce packets in my bag. “Save those for dinners,” Cosmo says. I pause for a second and consider his words, then rip one open and suck down the salty brown liquid. “This is amazing.” And I meant it. I hand Cosmo the other packet, and he agrees.

I don't want to get up and Cosmo looks equally reluctant to move, but we both know we have to keep going, especially if we still want to reach our cache tonight. We're just a few miles to where the trail turns again into a reliable dirt road, a point where we can’t trust the terrain.

We continue uphill on the trail toward a saddle. Just five more miles to go, and then it’s just five more miles to go, but all downhill! Downhill is usually my specialty, but once again, I can’t find a rhythm. Every step sends a fresh jolt of pain through my blisters, and my feet ache with a deep, grinding soreness. This route is wrecking my body. The pain isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s constant, slowing me down and stealing the joy from what should be an enjoyable descent toward the setting sun.

I pull over and futz (Cosmo keeps suggesting "Futz" as my trail name, and honestly, I don’t hate it) with my feet. I re-tape the blisters, adjust my laces, loosen some spots, tighten others, hoping for real relief. It never feels perfect, but once I plug into some podcasts, I find enough distraction to cover solid ground. My feet still ache, blisters, soreness, all of it, but suddenly this last stretch feels doable. Not entirely enjoyable, no, but doable.

We push on, hiking into the deepening twilight, then full dark, carrying a steady mix of excitement and anxiety. Just a little bit more, and there’s two buckets full of food waiting for us. Salivating, we try to remember what we stuffed in them. Will there be a full jar of peanut butter? Chocolate? A hot quesadilla? Who knows.. We also temper these dreams with the prospect that a bear dug these buckets up and ate everything inside. It’s very possible. We’d have to take the long road out, try to hitch a ride to town.

The winding dirt road feels endless under the beams of our headlamps. The familiar landscape dissolves into dark shifting shadows. A couple of times, I swear I see the end, only to realize it’s just an illusion.

Finally, a faint but familiar shape appears ahead. It’s the Adobe trailhead sign, this time, I’m sure. We made it! Our longest day yet, nearly 23 miles, and my body is zonked.

I think back to a week ago, burying our buckets here, completely unaware of how this section, this route, or this moment would go.

At the trailhead, Cosmo wastes no time and rushes over to the cache site while I set up the tent.

"Are they there?!" I yell, my voice breaking the silence .

"Got ’em!" Cosmo’s triumphant response echoes back, and a massive weight lifts off me. I look up and spot his silhouette emerging from the bushes, moving with the strong, confident gait of someone carrying buried treasure. He’s got a five-gallon bucket in each hand. With a satisfying thud, he drops them at my feet, then turns back to retrieve our extra gallons of water stashed in the trees.

The sheer volume of it all makes us feel rich.

Inside: six days of glorious food, an extra pair of shorts, new contact solution, and, oh my god, a liter of chocolate coconut water and a beer I’d completely forgotten I’d stashed. Thank you, past self.

The warm beer doesn’t sound appealing, but I crack open the coconut water, and Cosmo and I gulp it down on the spot.

Today hurt—but now it hurts so goooood.