Condor Trail Part 2: Dry Canyon to Santa Maria

Day 7 | May 21, 2025

I rinse my socks and shorts in some leftover water. My shorts are baggy now, stretched out and worn. We drink the Coca-Cola from our resupply buckets for breakfast and pack up. We re-bury our buckets to pick up later and leave Dry Canyon.

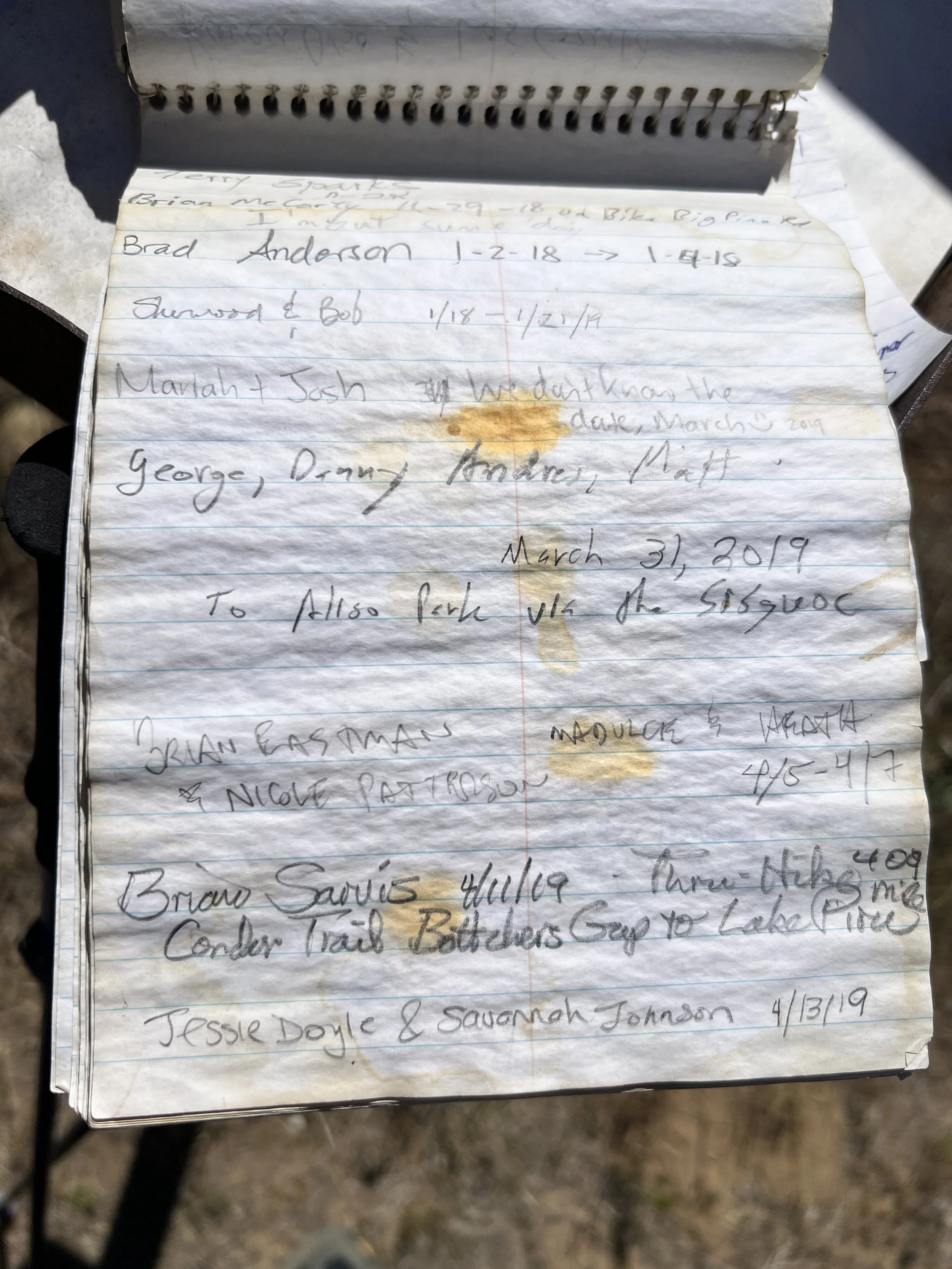

We reach the Santa Barbara Trailhead and sign the register. Flipping through the pages, we find Addison’s entry from a month ago. He went for the Fastest Known Time (FKT) on the Condor Trail, starting and finishing before we even began. He’s been a helpful source of beta, and we’ve been in touch throughout the trip. I keep thinking about how brutal it must’ve been for him to do this alone, in the cold, with rain and snow nearly every day. I still don’t know how he did it.

We head southeast, climbing up Santa Barbara Canyon. Poison oak is everywhere. Trying to dodge it feels both frustrating and pointless. I step carefully, twisting and ducking through brush, but it’s unavoidable. The thing with poison oak is that it doesn’t just stick to your skin, it clings to your clothes, gear, and anything it brushes against, and the oils can linger unseen for weeks. So dodging it isn’t just about protecting my body in the moment, it’s about avoiding contact altogether and staying mindful later not to touch anything that might have come into contact with it, to prevent spreading it around. This level of caution and careful cleanliness would be hard enough for me under normal circumstances, but it’s almost impossible while backpacking and wearing the same clothes every day.

At every creek crossing, we rinse our hiking poles and scrub our arms and legs vigorously, hoping the water will rinse off whatever oils we’ve picked up.

A huge black rattlesnake startles me, rattling as it slips off the trail and into the shade under an oak tree. I keep hiking, now hyper-aware of every stick that looks suspicious.

The climb up to Madulce Ridge is steep, brushy, and hot, but the views at the top are worth it.

We hike for a short stretch along Forest Road 9N11, wide, rocky, and lined with wildflowers. The sunset paints the landscape in warm hues. The poison oak is gone for now, and despite the constant soreness from blisters on my feet, I can finally enjoy the walking. We stare at the backside of Big Pine Mountain as we near Alamar Saddle and the end of this brief road section.

Dropping quickly from the saddle, we reach Upper Bear Camp and collapse into the shade. We’re now at the headwaters of the Sisquoc Wild and Scenic River, a place Cosmo and I have both been eager to explore. A cacophony of birdsong fills the air, loud and melodically overlapping.

Day 8 | May 22, 2025

I wake up sometime during the five o’clock hour, sunbeams pouring through gaps in the trees. My eyes are heavy and blurry, still caught between sleep and wakefulness, crusties tucked in the corners. My hand moves almost on its own, fumbling along the edge of my pillow until it hits the crinkle of my salty snack bag. I grab handfuls of potato chip crumbs, pretzels, sesame sticks, and whatever else I packed in my variety bag. Without even looking, I mindlessly pop it in my mouth and lick the salt off my fingers. It’s unconscious. Soothing. It’s good to be able to snack without fear of consequence.

The sound of the woodpeckers, relentlessly tapping, brings me back to the city with noises that resemble a construction site.

We descend through thick forest, following some semblance of the Sisquoc Trail, sharp switchbacks, waterfalls, ducks, the slap of stinging nettle, and the return of poison oak. We will be walking along the river for the next few days. The Sisquoc is the largest river on the Condor Trail.

We hit the 100-mile mark.

It’s a strenuous day. I keep losing the trail and getting stuck in a poison oak maze.

We reach Cottonwood Camp and pause to wash off the poison oak’s urushiol oils. The creek flows over smooth granite with shade and sun, almost Sierra-esque. I strip down and soak in the water, sunlight on my skin.

For a moment, it feels perfect. I step into a deeper pool and dunk my head, the quiet of underwater, the relief of finally stopping. I sink into the creek, soaking and scrubbing. I have no idea if I’m actually getting rid of the oils, but the rinsing (the ritual of it) feels necessary and mentally relieving.

The sun warms the rocks on the banks as we rinse our clothes and lay them out to dry. We make a little lunch. I could stay here forever. But I know I can’t. That quiet itch creeps in, not the oaky kind, but the self-induced mental kind, the part of me that can’t stop thinking about how far we still have to go. The worry hovers in the background while I try to relax. Have we hiked enough today? Made enough progress? Earned this kind of break? (Chill out, Larry! I know, I know.)

My body is sore, feet and lower back mostly. Today is mentally exhausting. The trail, if you can call it that, keeps climbing away from the river and dropping back down again, winding through thick shrubs and poison oak patches. The constant up and down, the endless scrambling through rough, tangled terrain, wears on my mind as much as my legs. Whenever the trail crosses the river, we struggle to find it again, invariably having to fight through poison oak to meet the trail for a hundred-yard semi-clear stretch before the pattern repeats. The miles are tough out here, really tough. If we keep up this 12-mile-a-day pace, we won’t reach our next bucket for six more days. That’s way too long. Didn’t we just deal with this issue? I don’t know if I packed out enough soy sauce packets to sustain me this time.

By sunset, we start climbing away from the river, and everything feels much less claustrophobic.

This part of the Sisquoc River Trail is peaceful and beautiful. We’re up above the river, which means scenic views and vast landscapes, free from the constant brushing and twisting through poison oak. I much prefer being above the canopy. The trail winds gently along the canyon. The hills are beautiful, their tops aglow from the setting sun. Still, I’m exhausted, and every step feels heavy. Please let us be close to camp.

I follow Cosmo along the overgrown single-track trail, not right behind him but close enough to catch the steady bob of his white hat weaving through the tall grasses and sage ahead.

With great relief and as night begins to fall, we arrive at South Fork Campground and eat dinner at a picnic table: Heather’s choice, African peanut stew with tortillas, soy sauce packets, and chili sauce. At the junction of the Sisquoc and Manzana Trails, South Fork is a well-developed site right on the river.

Day 9 | May 23, 2025

The day starts optimistically: clearer trail, less poison oak. I feel cautiously hopeful. This stretch along the Sisquoc seems to be a relatively more popular one (though we won’t see anyone all day), as backpackers can make a loop from Nira Campground along Hurricane Deck and Sisquoc. We hope that because of this, the trail will be in good shape from here to Manzana Schoolhouse.

We leave South Fork Camp and continue along the Sisquoc Trail. The valley opens up, and the river widens. The trail dips into the canyon, crosses the river, climbs into open grassy benches, then repeats: down, across, up, down, across, up. Each time we cross the Sisquoc, it gets harder to find the trail on the other side, up and down, search and hike. By midday, the pattern becomes annoyingly frustrating. But when we’re above the river, frustration melts. The sweeping canyon views and winding river below make this some of the most enjoyable hiking yet.

North of Big Bend Canyon, the guidebook mentions ruins of old homesteads appearing alongside the trail, but we don’t see much.

The ups and downs ease as the trail follows low along the riverbanks or winds through the wide floodplain.

One of the camps here, Mormon Camp, is so named because early visitors mistakenly thought the settlers were Mormon. According to the guidebook, they actually followed the teachings of Hiram Perserved Wheat, who prohibited tobacco, liquor, and animal fats and reportedly healed “by the laying on of hands” (Sarvis, 2021). At first, I imagined people on the ground, literally laying on each other’s hands. Or maybe someone lying down with their own hands tucked under their butt. What a weird way to heal. How does that even work? Then I realized it just means placing your hands on someone, like those mega-church preachers do, using the power of the Lord to heal someone else. Whatever the case may be, I wouldn’t mind a little hand healing for my aching feet.

By early evening, we’re less optimistic about making it to Manzana Schoolhouse. Out here, we keep having to readjust our goals and plans. That’s just the way these routes go.

We set a new goal: Water Canyon campsite. We hustle (as much as you can hustle across uneven terrain) to get there before sunset. We’re standing at the spot where the camp is supposed to be (according to both Gaia and OnX) but there’s nothing. No camp sign, no fire pit, no table, no tools. Not even a campable-looking spot.

“I’ll look over there,” Cosmo says, pointing to a large island across the river.

“Okay, I’ll climb up there,” I say, nodding toward a steep use trail leading to a flat, grassy bench.

“Find anything?” he calls faintly.

“Ummm… it’s flat up here. Could work. But I don’t think it’s the site.”

He can’t hear me.

I hike back down, and we reconvene. We look around a little more, then finally give up and continue down the trail.

We’ve now wasted quality time during sunset hours searching and not getting anywhere. We decide to keep hiking until we find a good looking spot to camp.

Eventually, we find the Water Canyon campsite, about 0.2 miles down the trail from where the map says it should be. It’s fine. Somewhat dark and oaky. There’s a smoke ring, a small table, and some occasional, suspiciously loud scurrying sounds coming from deep inside the massive tree trunk we’ve camped beneath. Maybe we’ll get lucky and it’s a crew of Keebler elves baking us cookies. More likely, it’s rodents doing their thing and plotting how to get to our snacks.

We finish setting up camp and head down to the river for our now-nightly full-body poison scrub off. This time, we pull out the Tecnu (poison oak wash and one piece of gear I’m very grateful we brought) and scrub vigorously, aggressively. That’s actually how you’re supposed to use it: imagining you’re trying to wash off something thick, like car grease, even though you can’t see anything on your skin. At first, the intensity felt a little over the top, but now that I’m itchy, the scrubbing feels like the one kind of scratching I’m actually allowed to do. The rash usually doesn’t show up for a few days after exposure, so the scrubbing is meant to prevent or lessen the reaction, but it’s always a surprise if it works.

I’ve dealt with poison oak before. Back in 2021 in Los Padres, I had the worst reaction I’ve ever had. It took time for the rash to show up once I was home, but when it did, it kept coming, itchy bumps, swelling, rashes everywhere, even on my face. I ended up going to urgent care for prescription-strength cream and steroids, which is definitely not something we have access to out here in the middle of the Sisquoc.

I’m hopeful the Tecnu will lessen the intensity of the poison oak reaction, but it’s too late for prevention, the inevitable has happened. Little red, bumpy rashes have appeared on my legs and a few on my arms.

I lie in my sleeping bag, itchy, listening to the crunching of critters in the leaves, the loud ribbits of the nightly frog party, and the scurrying inside the giant oak trunk. I remind myself that I chose, and continue to choose, to be here. Enjoy it dammit!

Day 10 | May 24, 2025

Morning arrives cloudy and cold, the sky overcast and the surrounding hilltops wrapped in mist. I groan, unzip the tent, and step outside to relieve myself. Fuck. I got my period.

I find my shoes and pick a few foxtails out of my gaiters.

I hike with most of my layers on until the sun breaks through the clouds and I am confident it is not going to rain.

We push on, hunting for bits of trail hidden beneath stubborn brush. When we do find the tread, it actually feels pretty nice and defined, comparatively, anyway. Our standards have drastically shifted out here.

Near Manzana Schoolhouse, Cosmo trips on a crack in the trail between two sharp rocks. He stands up swearing, glasses in two pieces, the frame snapped. Our gear is starting to stack up like casualties of war. He uses Tenacious Tape to hold his frame together, but it’s precarious at best.

We reach Manzana Schoolhouse and hike up a dirt road lined with lovely campsites, picnic tables, and fire rings under shaded oak trees. We pass a man setting up his camp and spark up a conversation. We haven’t seen anyone since Ozena Firehouse almost a week ago. We’re awkward and bumbling in conversation, but the man is nice. He says he’s jealous of our hike and we say oh yeah?

I nod and smile, genuinely glad to talk to someone other than Cosmo (no offense to him, but we really are alone out here). There’s a strange disconnect in these conversations, like we’re living parallel lives that almost touch but don’t quite meet.

Cosmo and I find our own picnic bench to take a break. The sun is fully out now, and we could use the time to dry some gear. Next to us is a pit toilet, privately enclosed by wooden slats. I head over to change my bloody pad. The toilet is only half enclosed and offers views of the Sisquoc. Of course, there’s poison oak growing near the seat. Relentless. I clean up without using the toilet and walk back to the picnic table.

“I think we should see if that guy has any extra charge,” I say. My batteries are already running low, and that familiar worry creeps in.

“Sounds good,” Cosmo replies.

The camper’s name is Sam, and thankfully, he’s almost done with his trip and has an unused battery pack he’s happy to lend us for a bit. Relieved, I bring it back to the picnic table, plug in, and wait.It’s the same old story: both Cosmo and I feel the internal tension between the urge to keep moving and making progress on the trail, and the practical need to pause and take care of essential tasks. It’s a mix of impatience and responsibility.

We sit beneath a tall tree and read. It’s picturesque. I rarely allow myself this kind of time on trail (or at home) to just sit and read. It’s nice. (The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers for me, and Stoner by John Williams for Cosmo).

An hour later, my phone is back to eighty percent. Thank you, Sam, wherever you are.

We follow an old roadbed along the river before reaching the beginning of Horse Canyon. As we leave the Sisquoc, we begin a new chapter, heading off into a notoriously difficult and trail-less section of the Condor Trail.

We spend most of the afternoon wading the creek. Progress is slow, but our attitudes stay positive, maybe because we’d been worried about this section for a while, and so far, it’s not too bad.

Mentally, we’re prepared, knowing this is a long canyon. At the start, it is open, dotted with scattered oak and sycamore trees. Low scrub and willows line the creek, which flows beneath grassy hillsides.

The canyon narrows the deeper we go. No signs of other hikers, just big animal tracks pressed into the mud.

The guidebook says to look for an old trail leading up to the higher hillsides. I like the sound of that. But no trail (especially not an old one) is obvious on the Condor route.

Every so often, we hallucinate a clear path or trail and scramble up a steep hillside. The climb takes time and energy, and we’re never sure how it will go. More often than not, we get turned back by an impenetrable bushwhack, sometimes with poison oak, sometimes without. We try this a few times, but it’s always slow and rarely fruitful.

The guidebook also says that if you can’t find the trail, it might be easier to follow the creek itself. Uh oh. We’ve read that before. I pull out the map on my phone to see where we are and have to zoom out uncomfortably far just to get a sense of scale. The book says we’re in this canyon for ten miles. Ten miles. The words echo in my head. Claustrophobia creeps in, curling tight in my chest (or maybe that’s just my cramps kicking in). Agua Blanca nearly broke me, and this canyon is longer and even more uncertain. The afternoon’s wading, however, is manageable and even peaceful at times.

We camp along the river, perform our nightly poison oak rinse and tick check, then coax a small fire to life. I rig a drying line for my period pads and a pair of socks. It’s getting harder to keep contaminated gear separate from clean, but I still hold onto the hope that my base layer pajamas are poison oak-free, and I can still catch a faint scent of laundry detergent lingering in the fabric’s creases. The rest of my clothes, though, are thick with sand and dirt—my shorts stretched out, my hiking shirt stained. It’s been 10 days since civilization, 10 days without a proper shower. Now I’m on my period. I feel itchy, dirty, sticky, and wet. It’s gross and uncomfortable. Trail life, babyyyyy.

Day 11 | May 25, 2025

Wake up, pack up, and continue curving north through Horse Canyon. The canyon is wide, our path weaving through a braided creekbed where thin lines of water cut between sandy stretches, scattered boulders, yellow-flowered deerweed, and hardy chaparral.

The openness of the canyon makes the hiking feel relatively easy.

Steep, brushy walls rise on either side, enclosing us in this wilderness and deepening the feeling of being truly out there.

The sky is clear, and our only shade comes from occasional oaks and narrowleaf willows. In a few spots, their branches reach out from the canyon walls in a scraggly tangle, casting cool shadows on the sand where we can sit.

After a couple of hours of hiking, I drag the back of my sun glove across my face, expecting to wipe away sweat and snot. Instead, when I glance down at the already tattered fabric (yet another casualty falling apart on this trail), there’s a bright smear of blood. Great, a bloody nose. We stop for a quick break so I can clean up.

The good times don’t seem to last long out here. Soon enough, we’re back to bushwhacking through thick brush and endless tangles of chaparral. My arms tire quickly from pushing branches. The stubborn limbs are tough and resilient, they don't break and refuse to give way easily.

We have to give each other space, careful not to crowd too close or the branches might rebound and smack the person behind in the face.

The next guidebook instruction says to take the most gradual slope to the right of a notch to reach the ridge. On the Condor Trail’s skewed scale, “gradual” apparently means a steep climb with grades hitting 45% in places. I push through dense chaparral as I start to climb, my hat and backpack bobbing through the brush like a cartoon character swallowed by vegetation. Clouds of pale yellow pollen scatter as I force my way forward, evergreen leaves brushing and thwacking my face.

The sun presses harder the higher we climb. There’s no water on this stretch; we’re both running low, and I’m thirsty. Sweat soaks my clothes, making everything clingy and uncomfortable. The thin fabric of my shirt catches on every thorn and twig, tugging and pulling as the brush tries to tear it apart. Sharp oak leaves, twigs and vegetation falls down the back of my shirt.

This section is one of the many cruxes Cosmo has been cautiously anticipating.

We meet at the saddle, Wyndham Gap, and collapse beneath a tall oak tree.

Cosmo pulls out his phone and shows me a video of a horrifying number of ticks racing up his pant leg.

“Ew! When did that happen?”

“Somewhere along this climb.”

I wasn’t even thinking about ticks on this climb. I jump up, shaking like the video is my own leg, and frantically perform a tick check. All clear.

We mix electrolyte powder into a cup of our rationed water and drink. I can feel every drop move through my body, but it’s nowhere near enough to quench my thirst. I’d love to stay in this shade all day, but we can’t. It’s late afternoon, and our pace has barely cracked a mile an hour.

We follow faint cow paths through tall, poky grasses, heading northwest down a hillside toward La Brea Creek. Finally, we get to refill on water. The irony is brutal after hours of scarcity— now there’s so much water we can’t avoid it.

Our route takes us straight through the creek, sometimes passable, other times barricaded by oak and willow branches arched over the water, reaching across like a net or booby trap. We duck, twist, and push through this obstacle course, slowing our pace even more. Sometimes we scramble up the banks, hoping for a clearer path, only to find poison oak clutching every inch, forcing us back into the water. The one step forward, two steps back rhythm of this route is maddening.

What the hell am I doing out here? I feel trapped, like the canyon walls are closing in, gripping me in a hug that’s too tight—suffocating. No quick escape, no side path leading out. We’re too far in to turn back, and honestly, retracing these brutal steps feels just as grim as pushing ahead. Deep in this remote canyon with no shortcuts, no easy way in or out. All that’s left is forward.

We’ve been slogging through the creekbed for about an hour, and I’m ready for another break. We’re close to Hiawatha Camp, but when we finally reach it, there’s nothing. No flat spot, no trace of a campsite, just an outdated, overgrown dot on the map.

We settle on a sloped patch of yellow grass, scanning carefully for poison oak before sitting down. It’s taken us all day to cover six miles. I can tell Cosmo doesn’t want to sit for long. Neither do I, but it feels necessary. Poison oak has inevitably rubbed onto some part of my skin or clothes. We do a quick rinse, scrubbing the spots that took the worst hits, hoping to wash away the oils before they sink in.

Every mile takes more time and energy than we have. The days feel shorter, and our food bags are getting lighter. I can feel the worry building, not just about poison oak, but about all of it, the weight of our choices and what we’re even doing out here.

About an hour after leaving Hiawatha, we start scanning for a decent spot to camp, but the route keeps us pinned in a narrow canyon where oak branches and brush press in from both sides. The creek takes up most of the ground, leaving no flat, dry, or clear space to camp. As the light fades, finding something workable turns urgent. Hiking in the dark is bad enough, but hiking in these canyons at night would be a disaster. On top of that, our route soon leaves the creek and starts a steep climb into the next crux.

My watch says our moving time for the day is barely three hours, while our total hiking time is closer to ten. We definitely didn’t take seven hours of breaks, it just shows how little ground we cover in this kind of terrain. It’s slow, grueling, and exhausting.

Another hour passes, and we finally stop waiting for a perfect site to appear. We scramble up a bank and find a semi-high perch. It’s not wide or open, but it’s better than anything we’ve seen so far. There’s poison oak, but it’s scattered and mostly avoidable if we’re careful. We clear just enough space for the tent, and that’s all there’s room for.

We climb up a bank and find a semi-high perch that feels like the best we’re going to get. There’s poison oak, but it’s scattered and mostly avoidable if we’re careful. We clear just enough space for the tent, and that’s all there is room for. As darkness settles in, the canyon comes alive. The crunching in the leaves grows louder, mixed with the sound of scratching and shuffling nearby. Our neighbor never reveals themselves, but we know they’re out there.

Day 12 | May 26, 2025

We get up and start hiking earlier than any other day so far, a small personal victory. I’ve been the slow one in the mornings, struggling to shake off the chill and get going, but today I’m proud. Hiking before 8 a.m., I feel a flicker of optimism, not just for a good day, but a successful one. With this early start, I’m hopeful we can finally make real progress.

The sun is out, Cosmo’s hat is falling apart, but our spirits are surprisingly high and the hiking feels no worse than usual. So far, so good.

The section of the Condor Trail between Hiawatha Camp and Roque Canyon is short but notorious, four of the hardest miles on the entire route. There’s no semblance of trail in this cross-country stretch. The route leaves one drainage, crosses two more (Salsipuedes and Stag Canyon), then finally drops into Roque Canyon. The area is still recovering from the 2009 La Brea Fire, and the chaparral has grown back thick, twisted, and relentless. Every mile demands our full attention.

Hiking in Los Padres is tough in general. Many mapped trails are unmaintained and overgrown. What looks clear on paper often disappears under thick brush, turning a simple walk into a slow, frustrating fight. But this stretch is different, there was never a real trail here. No footprints, no faint line to follow, just raw, untracked wilderness. Cross-country in Los Padres means bushwhacking, and bushwhacking in this terrain is its own challenge. The chaparral has adapted to dry, harsh conditions. It’s tough, full of thorns, spines, thick leaves, strong branches, and sharp spikes. Unlike other places where trailless terrain might be more open, here the plants form thick walls, snapping branches, scraping skin, snagging gear, and tearing holes in anything they catch. Beneath it all lie uneven ground, loose rocks, and the constant threat of ticks, snakes, and other critters. Hiking is slow, frustrating, and demands constant patience and care to navigate safely. We need every bit of good attitude we have as we enter this tough crux.

We work our way up the streambed, deep in the San Rafael Wilderness, surrounded by brushy hillsides and rugged terrain, no roads, no easy way in or out. The remoteness is palpable, like if I screamed, the sound would just get swallowed by the shrubs. After about a mile, the guidebook says it’s time to leave the creek behind and start climbing the hillside. I glance up at the thick, tangled brush blocking the slope. It doesn’t look navigable at all.

9:06am - 0.36 miles

The climb is dry, shadeless, and brutally slow, the kind of slow that traps you in a pace set by the terrain, a one step forward, two steps back kind of slow. I throw my whole body into every step, one arm shoving branches aside while the other grabs whatever I can to pull myself upward. The guidebook tells us to aim for a distant hill and climb through “open chaparral.” I look around and chuckle. If this is their idea of open, I’d hate to see what they call dense. I can already tell this is just the start of the hardest day on the trail.

Cosmo moves differently, perfecting his sway technique, leaning into the brush, almost surrendering to it, letting his body bounce between branches like a pinball. I try to mimic him but end up fighting the chaparral, tripping on hidden vines that snag my pack, clothes, arms, and legs until I’m tangled. I thrash like a fish caught in a net until I break free with a yell. Sometimes I manage a step forward; other times I get stuck and have to push around for another way. Every move takes energy: push, pull, squeeze through. I’ve never spent so much effort to go so little distance. Progress feels impossible.

This morning I was optimistic we’d make good progress, but now I’m not sure we’ll get anywhere at all.

The plants are taller than me now, wrapping me up whole. I can’t see Cosmo, but I know he’s ahead. We’re both grunting, searching for the easiest way through the tangled brush as we climb the hill. Every step feels heavier knowing how slowly we’re moving and how far we still have to go. I try to keep up with Cosmo, but no matter how much effort I put in, I can’t match his pace.

Our positive attitudes start to crack, frustration breeding snippiness. I know we have to dig deep to find patience for each other.

Then, whack! An evergreen branch smacks me in the face, the literal definition of bushwhacking: you push through, and the bushes push back. Its flat, paddle-shaped leaves scrape my eye, and I feel bits of dust and debris fly under my contact lens. I grit my teeth, knowing this will slow me down even more. I glance uphill. Cosmo’s already a good distance ahead, oblivious to what just happened. The space between us feels like it’s stretching, and I worry he’ll start wondering where I’ve disappeared to. I fumble to take out the lens (thankfully, I have spares). I set my pack down and carefully pour clean water into my eye, letting the cool rinse chase out the grit. I can’t risk infection or irritation, even though water is scarce. The next creek isn’t far, but at our current pace, it could be hours before we get there. I continue the climb with just one contact, figuring I’ll put in a new one when the right moment comes, though it never does.

Without that lens, my vision immediately worsens. Distant shapes blur into fuzz, smudging together like an impressionist painting. I squint, trying to pull details into focus, but it’s like looking through a fogged-up window on one side. It’s disorienting. The difference between my right and left eye is drastic, and my depth perception is skewed. If I focus on just my right eye, it’s kind of okay. Lucky for me, nearsightedness is perfect for bushwhacking, since all the action is smack dab in front of my face.

10:32am - 0.75 miles

I finally catch up to Cosmo, who’s waiting just ahead. He asks if I need to take a second, but I shake my head. “Let’s just keep going,” I say.

My attention shifts from one ache to another: sore, itchy, hot, wet, repeat.

This hike has become maddening. I keep scanning for what looks like a tiny clearing, just enough space for the next step, and throw every ounce of energy into pushing through, sometimes ripping my clothes in the process. But then I realize I’m in a dead-end circle, surrounded by dense brush with no way forward. It’s like being stuck in a funhouse of mirrors, where every door looks like an exit but just leads you back to where you started.

Cosmo’s sway technique keeps him moving, but I can’t find any rhythm. I look down and get smacked in the head by branches. I look forward and trip over vines snaring my ankles, but I never fall all the way forward, the brush is too thick. It just catches me, holding me in its spiky grip. Is that a good thing? I don’t know. I’m starting to doubt what we’re doing out here, and if it’s even humanly possible to make any real progress.

“Shit!”

“What?”

“My filter! It must’ve fallen out of my pocket in that last mess of branches.”

Cosmo sighs, backtracks a short way, and comes out holding it.

“Yes!” Finally, a win.

For the next mile and a half, we claw and crawl across the hillside, dipping into shallow canyons and scrambling back up the other side. There’s no clear line, just walls of stubborn chaparral that grab and push back with every step. The short washes between canyons are the toughest spots to climb out of. The ground is loose and unpredictable, a mix of sandy soil and old, crumbling roots that slip out from under you when you need them most. Being shorter than Cosmo makes it even harder. I can’t reach the same holds or get the same leverage, which turns each scramble into a frustrating challenge. Every move is a fight to keep my footing, with hands searching for holds that aren’t coated with poison oak.

We drop into Salsipuedes Canyon, cross the creek, and climb back up to contour across more hillsides. We’re bushwhacking on a slope, which takes quite a toll on the ankles. There’s no relief. Every time we claw our way to a high point, the view mocks us. Each ridge looks identical to the last, all twisted trees and brush-choked slopes. It feels like hiking through an optical illusion, and I’m still half-blind, wearing only one contact lens.

I glance at the map on my phone and yearn for the forest road just over these hills, a clear, easy route that could carry us where we need to go without this fight.

We cross another shallow saddle and make our way to the upper fork of Stag Canyon.

3:00pm - 01.90 miles

We pause at the spot where the Condor Trail veers north. Straight ahead, below us, Roque Canyon stretches out, our next checkpoint. Somehow, this spot feels like a haven, even though I have no reason to believe it will be. I don’t expect relief, I just desperately want this miserable chapter to end.

The Condor Trail makes a wide U-shaped loop around Roque Canyon to reach it from the north, passing Roque Camp where we know there’s reliable water. But it’s late afternoon, we’ve been hiking for over seven hours and have barely made two miles, with no guarantee the terrain ahead will be any easier or faster. It’s hard to look at where we’re going and willingly choose the long way around.

We were told about a shortcut, cutting straight across this canyon to hit the southern end of Roque, saving a few badly needed miles. From here, the route across almost looks promising. The brush even seems to thin out on the north hillside, teasing us with the illusion of, dare I say, “open chaparral?”. It’s a gamble, especially since we’re less certain about water on this side, but the thought of contouring all the way around feels unbearable.

We commit to the shortcut through the canyon below and start pushing toward Roque, Cosmo in the lead.

“Shit!” I look down at my hipbelt and notice the zipper is slightly open, the brush must have caught it. I reach inside and realize my headlamp is gone.

Cosmo stops and turns around. “What?”

“My headlamp. I think I lost it.”

“Really?”

We both freeze for a moment, knowing there’s no way we want to go all the way back through what we just fought. Cosmo backtracks a short distance and, against the odds, spots the tiny black headlamp on the ground. This section has a reputation for stealing gear, dubbed in the guidebook as the Roque Triangle, but not today, Condor Trail. Not today.

We push ahead, only to find that what looked like a gentle hillside from afar is actually a gauntlet of dagger-sharp agave, hidden until we’re right in the thick of it. Every few steps on this steeply sloped hillside, we’re forced to weave and dodge around stiff, spiky leaves lying in wait like clusters of landmines. It’s a new kind of misery, trading the suffocating grip of manzanita and buckthorn for precise, stabbing traps.

5:09pm - 02.50 miles

Despite numerous scrapes and scratches, and after nine hours of some of the worst hiking either of us has ever done, we finally reach Roque Canyon. Finding flowing water feels euphoric. We drop our packs and sink onto sun-warmed rocks. Miraculously, there’s space to lounge by the creek without poison oak encroaching, a true oasis.

I lean against a boulder, kick off my shoes, and stretch my legs. We filter water, mix drinks, and soak our sore feet in clear, cold pools. Butterflies float over wildflowers while tiny fish flicker below the surface.

“How far have we gone?” Cosmo asks.

I glance at my watch and laugh. “2.5 miles.”

He laughs too, shaking his head. “That’s what I would have guessed.”

Then his tone shifts, hesitant and thoughtful. He talks about Big Sur, how tricky it’s going to be, but his words come in half-formed fragments. I don’t catch everything clearly, but I sense the worry underneath about the terrain ahead. He says that Addison had mentioned that Big Sur had the worst bushwhacking of the whole trail. How can anything be worse than this? I realize he’s been carrying this weight for a while now, the logistical challenges there feeling more overwhelming after what we’ve just been through. Neither of us wants to face another day like today, that much is clear.

Our morale is low and we know it. But the idea of continuing through terrain like this is unbearable. The first thought of quitting vaguely makes its way into our conversation.The question, when to push through and when to walk away, is a tough one, and it applies to so many experiences in life. The idea of going somewhere else, somewhere we could actually hike, sounds pretty damn good. But quitting outright? That never felt like an option to me. What keeps me here if walking away is always possible? There’s something about commitment that holds me in place and forces me to move through the hard moments. But how do you know when sticking it out is strength, and when it’s just stubbornness?

There’s no point in making any big decisions yet. We still have to claw our way through several more canyons, ideally before our food runs out. We started this section with six days of food, and we’re already on day six. With 25-plus miles left and only about 17 total miles covered in the last three days, we’re in trouble.

Eventually, reluctantly, we leave our serene spot and continue down Roque Canyon in the late afternoon. As we start hiking, I realize I could’ve put in my new contact lens during the break. Oh well.

We spend the sunset hours wading through water and navigating narrow canyon walls. Roque Canyon stands out with its towering sandstone cliffs, patterned rock formations, and clear pools nestled among boulders. The thick riparian greenery—alder, oak, sycamore, and willow, feels both like a tangled maze and a rare oasis against the dry chaparral hillsides. In another time or place, this would be a beautiful and even enjoyable hike. But carrying the weight of everything we’ve been through, it’s hard to fully appreciate the beauty.

As the canyon deepens, the pools grow larger and the rock slicker. We scramble over boulders and wade through waist-deep water. Near sunset, we spot a small clearing with smooth granite benches and call it home for the night.

We wash our gear, clothes, and sore bodies in a clear pool, using a coarse clump of algae as a natural scrubber. Soon, everything is spread out on warm rocks to dry. It’s 7:30 p.m., and by the end of the day, we’ve officially covered just 3.86 miles.

8:14pm - 03.86 miles

After dinner, still hungry, we scroll through maps on our phones, making up alternate routes to our next resupply and calculating mileage.

Up until now, there’s been no choice, no intersecting trails or roads to bail onto. We’ve been stuck. Kerry Canyon, 4.8 miles away, is the first real decision point. Normally that would seem close but after today, I’m not even sure we can reach Kerry in a single day.

Cosmo reads through the guidebook, I look at maps. He mentions that before starting the trail, he remembers coming across a trail journal on Hike Los Padres that made Kerry Canyon sound like a heavy bushwhack. Damn.

I start mapping out alternates. “If we go south at Kerry instead of north, it’s about the same distance as the original route, maybe a little less. Two miles on Kerry Canyon Trail, then we hit OHV tracks and forest roads that would wind us to Highway 166. If those roads are in decent shape, we could be there tomorrow.”

Cosmo raises an eyebrow. “And if they’re not?”

“Then we’re screwed either way,” I say with a half-laugh.

I scroll through the guidebook notes and read some parts out loud, “Brookshire Camp to Willow Spring—‘easy to get off course,’ ‘old overgrown tracks, cow paths, and a little bushwhacking.’ The guidebook hasn’t used the word bushwhacking before. I don’t like it.”

Cosmo nods in agreement. “Dirt roads seem far more predictable. We’re out of food.”

I map out what we agree is a solid alternate plan, with the promise to reassess at the junction of Kerry Canyon. Still, I stare at the map, waiting for some miraculous burst of clarity, like Joseph Smith with his seer stones, something that will make me feel confident and even excited about what comes next.

“Why are you still looking at your phone? We have a plan. Put it away,” Cosmo says.

I appreciate the reminder to come back to the moment. It feels strange, sitting in this wild canyon with glowing screens, plotting digital escape routes. Then I look up: smooth granite, clear pools catching the last light, frogs tuning up for their nightly chorus. Our campsite is stunning, and there’s something quietly romantic about being out here together. For a moment, the beauty almost tricks me into forgetting how brutal the day was. Almost.

Day 13 | May 27, 2025

Leaving camp, the hiking finally eases up. The valley begins to widen, and with every step, it feels like the canyon walls that had been pressing in on us for days are slowly letting us go. The air feels lighter, our strides less forced.

We reach the junction of Kerry Canyon in about 2.5 hours (4.8 miles), which feels like a minor miracle compared to yesterday’s crawl. We drop our packs, sit in the shade, and make a second round of coffee.

My stomach growls as I rummage through my food bag: one lonely bar, a couple of dinners, a few salt packets, and a half-empty Mio. Cosmo crouches by the creek, silently filtering water. Neither of us says much. Energy is low, and morale is wearing thin like the soles of our shoes.

We agree on the alternate route, heading south through Kerry Canyon. The canyon is alive with frog parties, but in unsettling contrast, we spot more dead turtles than live ones—a grim detail that has followed us throughout this trek. Still, the conditions here are by far an improvement. We’re still wading through water, dodging poison oak, and brushing past the occasional tangle of thorns, but it feels almost easy by comparison.

The miles slip by faster, and when we hit our first OHV track, the landscape opens into wide, grassy patches with a faint but undeniable trail. It feels like freedom.

By 12:30 p.m., we reach La Brea Canyon Road, and to our sheer relief, it’s an actual dirt road, praise be! The temperature outside is hot and getting hotter. We collapse into a patch of rare shade, mix up another drink, and scrape the last stubborn crumbs from our food bags. The simple luxury of walking on a clear path feels almost euphoric. Maybe it’s the caffeine, or maybe it’s just the sweet relief of real progress, but our moods finally start to lift. We’ve covered 6.5 miles, and for once, it feels like cruising.

At 3:38 p.m., we pass a faded sign: Locked gate ahead. Five minutes later, we’re staring down Horseshoe Canyon and the edge of what looks like private land. According to Hike Los Padres, this is the border of the National Forest and ranch property. Ranches, the website warns, where owners “are not too fond of trespassers.”

Cosmo slows, scanning the horizon. “I don’t like this,” he mutters.

“What?”

“The private property.”

I follow his gaze and spot a couple of distant ranch houses, small against the beige sweep of California fields.

“I don’t like it,” he repeats, his voice low.

I shrug, too tired to think of another option. “What are we supposed to do?” Pine Canyon Road is our way out. We’re less than five miles from the forest road that leads to our resupply, and I don’t have it in me to care about property lines. We just have to keep moving.

Cosmo stays quiet, but his pace slows and his shoulders tighten. His unease radiates without a word. I start babbling about nothing, but he’s not listening. His eyes flick from the road to the fence line, like he’s waiting for a dog (or worse) to come tearing toward us. He’s had run-ins with biting dogs in the past, and rural trespassing is not his idea of fun.

Finally, he says, “This feels sketchy. I don’t like it.”

We stop hiking. “What do you want to do?” I ask.

“I don’t know.” He scans the landscape: the dirt road boxed in by barbed wire, a wide stretch of dry field beyond, and a faint wash snaking along the fence’s edge. He points toward the wash. “We could leave the road. Try to stay out of sight.”

“Really?” I ask, hoping there's a way I don’t have to leave the cruise control I found on the road.

“Yes. I would feel better.”

“Okay.”

We clamber over, trading firm road for rough, uneven ground. The wash is rocky, dotted with brittle grass and stubborn brush. Our pace slows. It feels absurd, sneaking through someone’s property while still fully visible. And honestly, the idea of having to “sneak” in the middle of the forest feels even more ridiculous. Private property. Pfft.

The route winds deeper into the canyon. The wash disappears, and the narrow path forces us back onto the dirt road whether we want to or not. Now the ranches press in closer, with weathered barns and houses lining both sides. It feels uncomfortably intimate, like we’re walking through someone’s front yard.

“Just act like we belong here,” I state matter of factly. “Maybe we live here. Maybe we are visiting family. They don’t know.”

Cosmo’s jaw tightens. He says nothing. I stop talking too.

We keep going, passing a few properties without seeing anyone.

Then, out of nowhere, a tractor rumbles toward us, a horse and dog in tow. Greg pulls up beside us, a man with a bit of a belly and the kind of tough, calloused hands that tell you he’s built everything he owns. His face is flushed, his white beard full and wild, and there’s a glint in his eyes, part friendly, part sly. He’s clearly been drinking, and still is.

A medium-sized black dog trots over, tail wagging.

“This is Charley Pride,” Greg says, pointing at the dog. “‘Cuz he’s black. And that’s Rowdy,” he adds, gesturing to the horse following lazily behind. “Say hi, Rowdy.”

Rowdy strolls past, unamused and unbothered.

We introduce ourselves, and Greg looks us over. “What the hell y’all doing out here?”

We explain the Condor Trail, how rough it’s been, how badly we need to get to our resupply boxes, and how we’re even considering hitching to town (a recent development). Once we hit Highway 166, it’s a straight shot to Santa Maria.

“I grew up in Santa Maria,” Greg says, “Went to all the schools there. Elementary…” He pauses, thinking hard. “What’s the next one?”

“Middle,” I suggest.

“Junior high!” Greg declares.

He launches into his life story (because, of course, no one delivers an unsolicited saga quite like an old white man who’s just found himself a captive audience). We learn about his family, that he’s building another house, and that he just spent the week with his son and grandkids.

I wait for a pause in his story and then ask, “Is it okay if we walk this road?”

Greg looks around, clearly confused by the question. “Why not?”

“Well, we saw the private property signs…but we didn’t see another way out…’ I trail off. Greg cuts in, confidence swelling now that he’s been granted some authority. ‘Y’all can hike here.’

“You’re sure other folks won’t mind?” I press. Greg pauses, grins, and repeats with confidence, “Y’all can hike here. No one will bother you. Tell ‘em Greg said so.”

Cosmo and I exhale, feeling some relief.

“Hiking the Condor Trail, huh?” Greg repeats as though he’s having an epiphany. he says, nodding as if he knows exactly what it is and the realization is sinking in more. He studies us for a moment.

“Y’all good on water?” he asks for the third time not pausing for us to answer. “Gotta have water. I always try to help people… gotta help people. Had bikers come through here before. They just appeared on the road just like y’all. Let ’em pitch a tent in my yard, brought ’em hot cocoa in the morning. Never seen anyone do what y’all are doing, though. Gotta help people.”

“We’re good on water,” Cosmo says. “We’ve got four liters.”

“But we’d take a beer!” Cosmo blurts out, surprising both me and Greg. I grin. Alright! Way to go, Cosmo.

Greg’s smile widens. “Yeah? You’d take that?” He fishes around in the cooler and hands Cosmo a dripping can. Then he looks at me. “You want one too?”

“Yeah, I’d love one, thank you!” I say, already grinning.

“All right,” he says, like we’ve passed some unspoken test. “If y’all need anything, you know where I live. Come knock on my door. You can camp here or whatever you need.”

“We appreciate that, thank you.”

He gives us one more squinty, assessing look. “You sure you got enough water?”

“We’re good. Thanks,” we assure him.

We continue down the road, less stressed now, and just tipsy enough for everything to feel slightly funnier.

When I get a flicker of cell service, I call a hotel in Santa Maria and reserve a room, giddy at the thought of real food and a shower and proud of my decisive action.

By the time we reach Highway 166, it’s 7:18 p.m., and daylight is fading fast. We cross the road, step off to the side, and stick out our thumbs. Cars come in little spurts, nothing for a few minutes, then three in a row, but nobody seems remotely interested in picking us up.

Five more miles stand between us and our resupply boxes, and yes, we could walk it, but our hearts are already set in the other direction, toward town food and a bed.

A Forest Service truck slows to a stop and rolls down the window. One ranger asks with a mix of curiosity and concern, “You two okay?” We give them the quick version, the Condor Trail, our resupply, the reserved hotel room. “We can’t give you a ride,” they say, almost apologetically, like they wish they could but the rulebook won’t allow it. “You good on water?”

I stifle a laugh. “Yes, we’re good,” I assure them, wondering why everyone out here is obsessed with our hydration levels.

“Alright then. Good luck.” They wave and continue to their station, leaving us alone again on the empty highway.

We stick out our thumbs as cars pass by. Some drivers don’t even glance our way, like we’re invisible. Others wave, and we can see their cars are legitimately packed. Then there are the ones who smile and wave, arms raised in helpless apology, like they’d totally stop but their car simply refuses to cooperate.

The real panic hits when I realize we need to cancel the hotel before they charge my card, and of course the cell service here is a cruel joke. We find one tiny hotspot on the road, but every time we get a few sentences in, the call drops. Poor Thomas at the hotel front desk answers over and over as we keep calling back, both of us shouting into the phone like it’ll improve the connection. Sometimes we make a little more progress, then right when it gets important, “I’m sorry, ma’am/sir, I can’t hear you.” Click.

Cosmo and I take turns calling, pacing the highway shoulder searching for a signal. I walk down the road, face glued to my phone waiting for a bar when I hear a shout.

“Hey!” I look up. Greg is waving like we’re old friends from his tractor across the highway at the end of Pine Mountain Road.

“Y’all still here?” he jokes.

“Looks like it,” we reply.

“My son didn’t stop for you?”

“Your son?...No. Nobody has stopped for us.” we shout back.

“Son of a bitch,” he mutters. “I told him to get you guys! He just left for Santa Maria.” My stomach drops, that was probably our one chance.

Greg watches us for a moment, squinting like he’s still deciding if we’re hopeless or stubborn. “If you don’t find a ride,” he says, “just come on back to my place.”

“Thanks, Greg!”

I glance back at my phone and keep trying to call the hotel. I hold my hand up to the sky like it might help, then lower it quickly to check the screen.

“Wait, I’ve got a bar over here!” I yell.

“Don’t move, don’t move!” Cosmo shouts.

Of course, the second I shift or breathe wrong, the signal vanishes. Sometimes we make it through the automated maze, get as far as “Hi, I’m calling about my reservation...” and then silence. Dropped again.

We call back. “Thomas! Hi, it’s us again, the hikers…hello? Thomas?” Dropped again.

Poor Thomas deserves a medal for patience. Every time we call back, he answers with the same calm tone, as if he’s not dealing with two feral hikers losing their minds on a rural highway. I can’t take it anymore and rip into one of our last cold-soaked dinners like a raccoon digging through a dumpster.

Suddenly, brake lights. A car slows and pulls over. Yes! I grab my pack and hurry to the window. A young woman leans out, looking concerned.

“I’m sorry, I can’t give you a ride,” she says and I swear both Cosmo and I physically wilt. “I live around here and just wanted to make sure you’re okay. Are you okay?”

Confused, we nod. “Yeah, we’re good.”

“Nobody tried bothering you?”

“No…” we answer, puzzled.

“Okay, good. This highway attracts some bad people, so I just wanted to check.”

“We’re good.”

“Okay, be careful.” She drives away.

I look at Cosmo. “That was weird.”

“Super weird,” he agrees.

Darkness is settling, and with it, our optimism. Not only will we miss the hotel, but now I’m sure they’ll charge us an extra fee. “Screw it,” I say. “We might as well pay for an Uber. We’re spending the money anyway.”

As Cosmo stands still, arm raised to the sky, desperately trying to hold a single bar of service to get the Uber app to load, a police car slows and pulls over. The sirens flash once and my stomach drops. Shit! Is hitchhiking illegal? Cosmo puts his phone down and stands next to me and the cop car.

The officer rolls down his window. “What are you two up to?”

We launch into our story, the Condor Trail, running out of food, just trying to get to a hotel.

“I got a few calls about people standing in the middle of the highway waving cars down. Folks said you might be in trouble. Are you okay?”

“Yes, we’re fine,” I say, relieved we’re not getting a ticket. “Just trying to get to town.”

“You’re trying to get to Santa Maria?”

“Yeah, to the Motel 6,” Cosmo adds.

The officer pauses, then, like some bizarre twist of fate, says, “Alright. Well, I can give you a ride.”

We stare at him, stunned. “Wait, really?”

Getting a hitch from a cop? This is a first for either of us.

“Yeah. Hitchhiking on this road isn’t safe. I can take you.”

Cosmo and I snap out of our roadside stupor, grinning at each other as we spring into motion. We grab our gear, stumbling over rushed thank-yous while blurting out how we were about to blow a small fortune on an Uber.

“It’s all good,” the officer says. “This is an easy call compared to others I could get.”

I swear we would’ve hugged him if it weren’t for the gun and baton on his belt.

He tosses our filthy packs into the trunk and opens the back door for us. We slide in behind the metal grate, instantly looking like two petty criminals.

As we drive, the officer asks about the trail and shares some of his favorite spots in Los Padres. I nod along, but my gaze stays fixed on the window. The landscape shifts, the valley opens, low mountains glowing gold and red in the sunset. The road winds through oak-studded hills and wide grassy fields, the whole scene drenched in warm light. I catch faint whiffs of salty ocean air, and for once, I’m happy to be behind a window, separated from nature, instead of clawing through brush and poison oak.

Cosmo nudges me and gestures at the dashboard screen. “That’s us,” he whispers, grinning, pointing at the screen that says something about “two people looking distressed.” I can’t see it from my side, but he looks oddly proud of our cameo on the police log.

“I wonder why no one stopped,” I murmur. Maybe it confirms what the local girl said earlier: Highway 166 has a reputation, and people are wary of hitchhikers.

And just like that, we get the kind of trail magic you can’t make up. Our first cop hitch.

We pull up to the hotel like accidental celebrities, turning heads as we step out of the back of a cop car. Before driving off the officer looks at us sincerely and says, “Hey, just… please don’t hitchhike on that road again, alright?” There’s a gentle tone beneath the warning, like he really wants us to be safe without sounding too strict. We nod and promise to comply.

We walk into the hotel lobby, and Thomas at the front desk chuckles softly when he sees us. He already knows exactly who we are. We apologize for all the calls, but he just waves it off and gets us checked in.

Inside the room, we drop our packs and immediately start talking about food. There’s nothing nearby.

We walk to an overpriced grocery store, but the options are bleak. “I’m going to Burger King.” Cosmo says.

I buy a couple of avocados and some greens, then meet up with Cosmo inside Burger King. We sit in a booth and wait for our food. I pull out my phone and start scrolling through more trip reports and trail conditions ahead.

Why are we doing this? Not just this moment, but the whole trail. The blisters, the hunger, the days when we can barely hike. The extreme lows, the unmatched highs. I know Cosmo’s nervous about the second half of the route. The conditions in Big Sur sound worse than anything we've seen so far. I hear his concerns, but I can’t wrap my head around something worse than what we’ve already been through.

“Will you text Mugwort, please?” I ask.

“What for?”

“Because I want someone to convince us to stay out here. I need a morale boost.”

We re-read an old text message Mugwort sent Cosmo. He loved hiking the Condor Trail. It also sounds like he skipped around a lot of the most brutal sections. We open another message from Addison, sent a couple of months ago. His words come with caution: Big Sur is no joke.

We get back to our room and inhale the burgers and fries anyway, gone in minutes.